'Deep, Dark & Dusty' Full Documentary Transcript

By Matt Scofield

January 05, 2019

January 05, 2019

This page is more than six years old and was last updated in February 2021.

'Deep, Dark & Dusty'

In 2002 MVP Video Productions released their film 'Deep, Dark & Dusty' on VHS and DVD. The 115 minute documentary became a must-see piece of research for those interesting in exploring the secret of Corsham's network of underground tunnels. The film contained a rare and unique look and some of the formerly top secret wartime bunkers under Corsham.

Now 17 years on, the DVD is no longer in production and as it contains rare information, which isn't readily available anywhere else on the internet, it seemed like a good idea to but the full transcript of the film online.

One of closing lines in the documentary, delivered by narrator Jeremy English, states that "today there's a serious threat that this history will be lost forever, old quarries are in danger of being sealed and forgotten." So, in the spirit of preserving and making available this special part of British history forever, the full transcript of the film is available below.

This programme brought viewer sights that have seldom been seen and some that may never be seen again. Of course today some of the information contained within the film is out of date, but the historical information on the history of Bath stone quarrying and the later military uses of those quarries is still as interesting today as when the film was originally released.

MVP followed up this release with a second DVD entitled 'Lifting The Lid On Box Hill' two years later.

'Deep, Dark & Dusty' Full DVD Transcript

What have the following got in common? A bottle of wine, 300,000 tons of high explosive bombs, the city of Bath and a motorbike. The answer is Bath stone.

Hello, I'm Jeremy English. In this programme we're going to tell you the story of Bath stone, its quarrymen and their quarries. And, some long hidden secrets of the glorious rolling hills of Wiltshire and North-East Somerset.

The story of Bath stone and its quarrymen, who laboured underground for long, dark, arduous hours, has seldom been told. The golden coloured granular limestone they quarried was formed during the Jurassic period, approximately 150 million years ago.

A band of stone called great oolite exists within these Jurassic rocks, giving a useful working bed of Bath stone, that is on average 18 to 20 foot thick.

Bath stone is a freestone, this means it can be cut or squared in any direction, but it must be laid in building construction in the same way as it did in the ground from where it came.

Some of the earlier users of Bath stone were the Romans. The town of Aquae Sulis is today better known to us as Bath, but it was during the Roman occupation of Aquae Sulis in the late-first century that they discovered Britain's only natural hot spring, and so built the now world famous baths.

They were used by the Romans for approximately 400 years, with the thermal waters having a comfortable temperature of 46 degrees. Rising in the adjacent King's bath, and then flowing into the Roman bath.

The Roman remains of the great bath survive to a height of five feet and are built of Bath stone. It's now surrounded by a Victorian terraced structure, which also contains the ruins of the temple of Sulis Minerva, the Romano-Celtic Goddess of the springs.

To acquire the stone for the building, the Romans dug open quarries on the hills surrounding Bath. Little evidence remains of the Roman sites today, but this view of the old Seven Sisters Quarry at Bathampton gives the general impression of how it may have looked.

The long-abandoned Springfield Quarry was the largest open quarry in the immediate vicinity of Bath. This view shows the quarried area exposed by the removal of some two and a half million cubic feet of stone.

It also illustrates how near to the surface was the stones strata in this area of Combe Down. It's believed that the stone from this quarry was used for the building of Bath abbey.

Approximately 600 years later, in 675 AD, legend has it that a monk, St. Aldhelm was out riding. Here at a place called Hazelbury near Box, he threw down his gauntlet and said to those riding with him, “dig here and you shall find great treasure.” Meaning the valuable Bath stone.

His name and gauntlet were used as the trademark for Box Ground Stone, the stone from the first quarry and Hazelbury was used for the building of St Laurence's Church at Bradford-on-Avon, which still survives today as the oldest church in England.

Hazelbury stone was also used at Malmesbury Abbey, which St. Aldhelm founded.

Bath stone was also used to construct the tithe barn at Bradford-on-Avon, this being built in the 14th century by the abbess of Shaftesbury. Its massive timber joists and stone tiled roof cover a granary more than 167 feet long by 30 feet wide.

Lacock Abbey was built with Bath stone from Hazelbury, as were many large buildings in the area at that time. It's a thought that without Bath stone the abbey might not have been built and that William Henry Fox Talbot, one of its latter day occupants of the 1830s, would not have cared out his pioneering work into photography, to which this film owes its origins.

The 16th century Longleat House, the family seat of the marquess of Bath, was also constructed with Hazelbury stone.

The next phase in the Bath stone story came in 1710 when a Cornish man name Ralph Allen moved to Bath. By the age of 19 he'd become post master, revolutionising the postal services in the city. From this he made a lot of money, which he invested in land and development.

If the golden Bath stone has had a golden age, then it must surely be the Ralph Allen period. In 1726 he acquired the stone quarries at Combe Down, just as the building boom began in Bath. From his quarries came the stone for building the magnificent Georgian city as we know it today. Together with the architect John Wood and the dandy Richard Beau Nash, Allen made a second fortune.

A year later the River Avon navigation from Bath to Bristol was opened, so Allen acquired land on the river bank at Dolemeads with a view to exporting his stone by boat.

Adjacent to Bath abbey, this narrow Palladian style townhouse in Lilliput Alley was Ralph Allen's original home in Bath. Today, it's surrounded by modern-day Bath buildings, but it's still possible to view from here the slopes of Claverton Down and the folly that Allen built there called Sham Castle. As the name implies, it's simply a facade. Its only purpose was to enhance the view from his townhouse windows.

He then built the Ralph Allen tramway, now the busy A367. The tramway brought about a 25% reduction in the cost of the stone. The grand stone pillars mark the of the decent to Dolemead Wharf.

In 1735, Allen commissioned John Wood to build him a superb Palladian show house called Prior Park. It was a fine example of what could be done with the stone from his quarries. Allen invited prospective clients to the house so they could see the fine, finished qualities of the Bath stone. He had by now accumulated great wealth and entertained many of the great personages of the day.

The house is flanked by two large wings connected by covered pavilions. The western wing contains a breakfast room and bedroom, much favoured by Allen as an informal retreat from the mansion. The eastern wing was used for stabling, coach storage and as a pigeon roost.

Today this magnificent building is used as a college. Despite it suffering two major fires in its history, the impressive internal fixtures and fittings were restored and are maintained in immaculate condition.

The grand staircase from the library down to the entrance hall is still overseen by Allen, whose portrait hangs on the stairs. The entrance hall has fine Corinthian columns and ornate ceilings. Leading through from the entrance to the portico, there are grandiose views to be enjoyed over the Widcombe Valley and the city of Bath.

With the popularity of the stone growing, he opened another quarry on the adjacent Combe Down, called the Firs.

Ralph Allen was a benevolent man, building cottages for his quarrymen and masons. He also gave money and stone for the building of the mineral water hospital in Bath in 1738. He died in 1764 at the age of 71 and is buried in a pyramid-topped tomb in the nearby Claverton churchyard.

Over the next 100 years many new quarries were established at Box, Westwood, Corsham Down, Monkton Farleigh and further along Combe Down.

In 1810, the opening of the Kennet and Avon canal moved quarrying activates further up river to Avoncliff, Conkwell, Dundas and Winsley. Many of the quarries built inclined tramways down to the canal to enable transportation of stone eastward to Swindon, London and Oxford.

This tramway location, which survives today albeit without its rails, served Hampton Down quarries at Bathampton. It had an average 1:3 gradient and worked in conjunction with horsepower and returning empty wagons, which were pulled up the hill as the loaded ones went down.

The year 1836 saw a new chapter for the Bath stone story open up, the redoubtable Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel was contracted to build the Great Western Railway.

In order to build the last 24 miles of the railway, it was necessary to tunnel under Box Hill, a task which had been quoted as being practically impossible to do.

This tunnel, nearly two miles long, cost £100 for every yard advanced. Its construction was a great feat in those days of early railway engineering and when completed, it was the largest railway tunnel in existence.

To be able to constructed the tunnel, 14 shafts 30 foot diameter and varying from 70 to 300 foot deep were sunk along the alignment of the tunnel. Theses shafts were used as bases from which excavating operations proceeded.

After construction, seven of shafts remain to afford through ventilation to the tunnel and to be able to drain away the water ingress to the tunnel from above.

During the construction of the tunnel the builders used a ton of candles and a ton of gunpowder every week. This was to put the small village of Box firmly on the map and the task took more than five years to achieve, employing over 4,000 workers including many local quarrymen. Sadly the tunnelling claimed the lives of many men.

The Tunnel Inn, situated on the top of Box Hill, not only served pints of beer, but also acted as a boarding house and mortuary for the Brunel workforce. The dead were brought to the surface via the access shafts, stored in the mortuary and then removed later by horse and cart for burial. The building still stands today, but as a private residence.

Whilst tunnelling through Box, Brunel's workforce found endlessly large seams of Bath stone. Following the opening of the railway in 1841, the local quarrymen opened more quarries in the Box Hill area to extract the new-found source of stone.

The tunnel descends on a gradient of 1:100 and is of such alignment that it's said that on Brunel's birthday in April it's possible to see the Sun shining through the complete length of the tunnel. Brunel was indeed a very clever man.

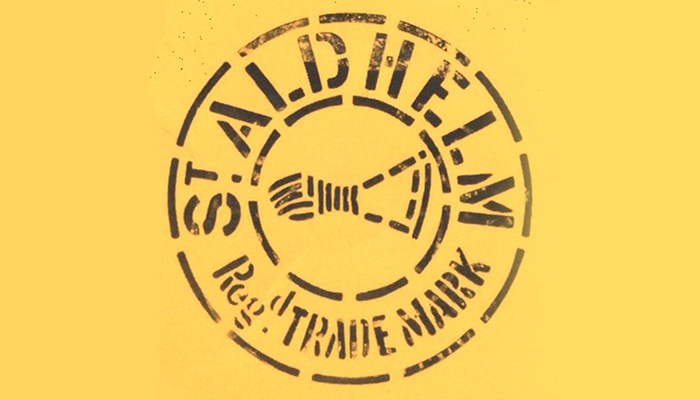

The new quarries on Box Hill each developed in a haphazard way. Each of these arrows depicts a new quarry entrance. The quarries expanded their underground roadways randomly, soon meeting up with each others workings. Many joined together and in the centre of the Box complex is an area known as the Cathedral.

So called because of its sheer size, the Cathedral measures 190 feet long, 72 feet high and 25 feet wide. To be able to bring you these exclusive images it was necessary to take underground a heavy generator, this was achieved only by the kind assistance of the local quarry guides, who struggled and suffered through the many passageways to and from the chamber.

In the ceiling of the chamber is a large shaft to the surface. Between the years of 1822 to 1850, the stone was removed from this chamber by hauling it through this hole. The ceiling is only 20 foot thick in places, there are some cottages at the surface partly built on it. Because of the intense lighting, it is the first time that even the guides have been able to view the chamber in its full magnitude and see things that have probably never before been seen.

This view in the Cathedral clearly shows the different levels taken out as the chamber deepened from above to eventually join the passageways below.

Two other vertical surface shafts exist in the Box complex. The Box No. 4 shaft, which as seen here has been strengthened by the Ministry as an air intake and Webb's Stores shaft. This stone staircase leads up to what was an iron ladder within the shaft, giving a 60 foot vertical climb to the surface. This was the entrance that the quarrymen used when going to and from work.

In 1844 Randell & Saunders, who owned the Tunnel Quarry at Corsham, made alterations to their entrance to the quarry to accept a standard gauge railway line. The Great Western later laid an additional railway line into Corsham station, running separately from their main line. Transportation costs now dropped even further, with Corsham railway stone yard becoming an export base to many parts of the world.

By 1870 the stone industry in the Bath area was well established, with individual companies becoming more powerful. Randell & Saunders, Pictor & Sons, Stone Brothers, and Sumsions all owned parts of the growing quarry industry that was rapidly developing in the area.

A further 20 years on saw a total of 12 firms operating in the area, all in fierce competition. In 1887, most of the companies amalgamated into the Bath Stone Firms Limited. Seen here as their newly opened stone yard at Corsham station.

By 1900 the combined output was three million cubic feet of stone a year and the quarries boasted around 60 miles of underground roadways in the Corsham area alone.

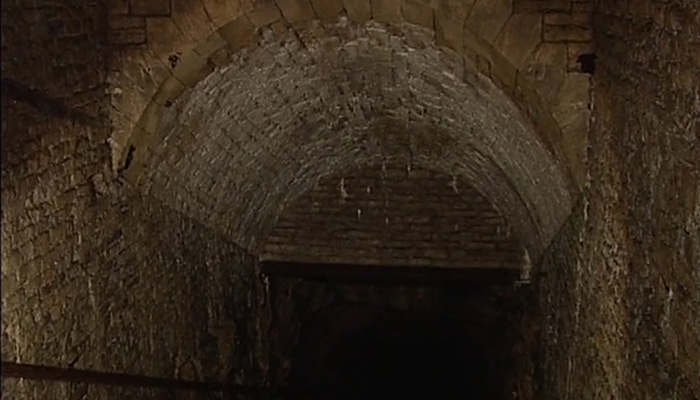

So, how was the stone run from the ground? An entrance like this, an adit, was excavated. It's also known as a slope shaft.

This gave the quarrymen access to the beds of workable Bath stone and also a means to get cut stone out to the surface. The beds of oolite stone can generally be between one and seven feet in thickness. Above the layer of Bath stone are rag-stone and forest marble, which generally form the ceiling of the workings.

The quarrymen followed the good stone, leaving pillars of the smallest possible size to support the ceiling, but leaving much larger pillars where the stone was faulted or of poor quality.

The procedure for removing the stone is same now as it was when quarrying started. Firstly, a cut is made at ceiling level horizontal to the ground. Next two vertical cuts are made. Wedges and chips are then driven in to displace the centre or “wrist block” on its natural bed line. A Lewis pin is the inserted and the wrist block is removed, which then allows access to the rear wall.

In the early days of quarrying the cuts were made by using picks, this was a hard manual task, taking many man hours to achieve. The picker would use picks of differing lengths to achieve the work which left a distinctive picking mark just below the ceiling.

By the early 19th century, a jadding bar was introduced. This long-handled chisel-like tool was used to make the cuts deeper into the heading. The bar also allowed better cutting into the back corners, where the pick was unable to get. Then by using large levers, the stone was broken away. This example of a jadding bar slot is in Box Quarry.

The jadding method also left readily recognisable marks in the quarries, this allows the date of the working to be easily established. The stone blocks produced were generally small in size, it was only with the general introduction of saws in 1840 that stone block size increased.

The large, wide-bladed, two-handed saws gave a near perfect finished face to the stone. The ceiling cut however had to be deeper, up to five feet so the saw could be inserted.

Lit only by candles and later oil lamps, the sawyers would cut the stone all day. Using a tin of water with a hole in to lubricate the cut, they sectioned vast amounts of stone.

The picker would be paid by the area of roof that he picked, but by sawing at an angle, the sawyer could increase the width of the lower block, because he was paid for the stone he cut, thereby earning him more money than the picker. This practice was known as pillar robbing and resulted in downward tapering pillars to support the ceiling.

Some sat on small, one-legged wooden stools, so if they fell asleep while sawing, they would fall off the stool and therefore wake themselves up.

Once cut and freed, the stone blocks were moved around by using a crab winch. This unique, iron framework trolley type, made by Randell & Saunders, is seen here in Box Clift Quarry.

By about 1840 cranes were more commonly in use. These cranes were normally managed by the quarry ganger, who employed his own men and was paid by the quarry owner for the cubic footage of stone brought to the surface. Many fine examples of these cranes still survive in the quarries.

Crane sites are easily identified by these distinctive square holes in the ceiling, known as chug holes, which housed the bearing for the crane to turn on.

Using wire ropes, the cranes would drag the stone from the working face to a loading platform, then on to a wheeled cart or narrow-gauge railway wagon. Today the stone bares the scars of the many cuts made by the ropes when the heavy blocks of stone were moved around.

As the working face extended further into the seam of stone, the cranes would be taken apart and moved to new locations in the quarry. They could also be moved around by using the crab winches and rail trollies.

This particularly fine example of a crane in Freshford Quarry is still in working order and was demonstrated to us by the mine manager.

To move the stone out to the surface, horses were used. These images were taken at Westwood Quarry in the 1900s. Here at Westwood Quarry the wheeled tracks of the horse-drawn carts carved grooves into the floor. These show especially on the bends where the tilting of the cart, due to its weight, made deeper grooves.

Horses were widely used underground, they hauled the stone from the headings to the bottom of the slope shaft. Some quarries even had underground stable accommodation, with the horses being brought to the surface at the end of every week. Others were stabled on the surface. A social horse box cart was made so that horses could be hauled up the slope shaft.

In the northern section of the Box workings is Clift Quarry, its entrance is alongside the A4 Bath Road. A narrow-gauge railway carried the stone out from the quarry and up the hill, along what is now the edge of the A4. The train then reversed and travelled back down the hill, above the quarry entrance and then further down the hill to the railway sidings at western end of Box Tunnel.

Theses buildings which are now private residences were the former maintenance workshops. The stables for the horses used in the quarries still survive alongside the main road.

Unusually a small steam locomotive was used in the Clift Workings, today this day the ceilings of the main passages in Clift still have the line of soot marks made by the locomotive.

In this area the locomotive would fill with water from the stone built water tank that was filled from a well opposite. Here the roof is extensively stained as the loco would have stoked up its fire at this point.

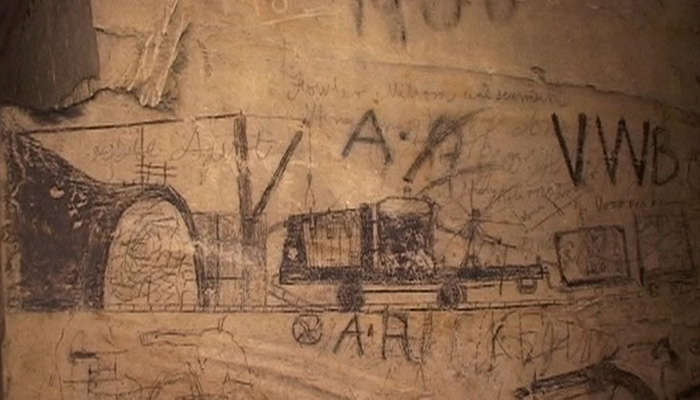

Our quarry guide and a member of our production team walked the route that the loco would have taken into the quarry. George Mould, the regular driver of the loco, must have had some time to kill, for he made this drawing on the wall of his locomotive. It clearly shows his hand on the regulator handle, the three cylinders in line, the vertical boiler and high-level chimney. It's coupled to two wagons, each with large blocks of stone on them.

The quarry entrance is also depicted, showing the iron fence over the entrance, which was the tramway down to Box Hill and a crane situated directly outside the entrance.

It also shows the diverging line leading in to the adjacent stonemasons' buildings. This newspaper cutting verifies how accurate his drawing was.

Advertisement ‐ Content Continues Below.

In July 1870, a fundraising appeal was held in a bid to replace the roof on the nearby Wesleyan chapel on Box Hill. Over a period of two days the public was treated to rides behind the locomotive around the quarry. Paying thruppence for a second class and six pence for a first class ticket.

When the steam locomotive came to the end of its working life, so did its driver George Mould, who was pensioned off. The steam loco was replaced by horses. The chapel is situated next door to the village pub, aptly named the Quarryman's Arms.

It can be thoroughly recommended and was well used by the production team the making of this video.

Many of the narrow-gauge railway systems do not survive today, but the sleeper holes are still evident.

As work progressed in the quarries, inferior faulty stone and cutting waste was left behind in large quantities. This was neatly hand-packed into the previously quarried spaces and around pillars to within a foot or two of the ceiling.

During the winter months the cut stone was stored underground to protect it from frost. An example of this survives in Box Quarry, cut stone being trapped by a ceiling fall and remaining so ever since.

The stonemasons who normally worked on the surface, were not fully used during the winter months, so they were brought down to shore up and build supports in areas with bad ceilings or faults. The result of their work can be seen here Box Quarry. All carried out with great skill and care, resulting in architectural features that reflected the period. Remember, this was all carried out by hand.

With the onset of World War One, the Bath stone industry started to decline. With me being called up to server their country, manpower in all industries dwindled. The demand for building stone dropped and many quarries had to close.

German Zeppelins were now dropping bombs on English soil and the War Department suddenly realised their surface stockpiles of ammunition, spread throughout Britain, were vulnerable, like this store a Chilwell.

Smaller stocks were distributed throughout the UK alongside roads in small corrugated sheds. Rail head storage was usually located in forestry, at sites such as this one in Savernake Forest.

With great urgency an underground store had to be found. The Ridge Quarries at Neston in Corsham, owned by the Bath Stone Firms was immediately requisitioned by the Ministry of Munitions and a new chapter in Bath stone quarrying history was begun.

The Ridge Quarries comprised of the 1875 Old Ridge and the 1881 New Ridge, which were linked underground to the adjacent Monks West Quarry. Together they offered 12 acres of storage space.

Here in the Old Ridge Quarry we see some of the 96,000 tons of waste stone that had to be removed from the New Ridge Quarry to make room for the explosives. Once cleared, the site was divided with a wall.

They usable six acres then had its roof shored up so that cordite and TNT could be stored. The store held 16,000 tons of explosives. The quarry had a military two-foot gauge Decauville railway track laid in a good part of the workings. This severed raised stacking platforms.

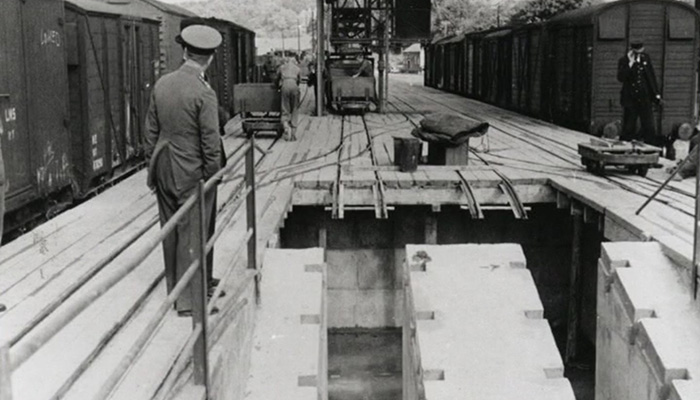

A quarry tramway connected Ridge with the Great Western railway at Corsham, one and a half miles distant, seen here in quarrying days, this was utilised to move the explosives. Ridge was capable of dispatching over 500 tons of explosives a day.

The demand for stone fell after the Great War because of the increased use of concrete in building and the general depression of 1920s and 30s. Stone reserves were exhausted and many quarries became uneconomic to work. Some were let for other commercial use, such as mushroom farming.

By 1935 only seven quarries were still in production, but the next major development in the history of the quarries in the Corsham area soon arrived.

Central Ammunitions Depot

By the mid-1930s the War Office could see that another conflict was looming. Already owning Ridge, they requisitioned more Bath stone quarries at Eastlays, Monkton Farleigh and Tunnel. These huge underground areas would be required to prevent hostile aircraft from bombing the country's mounting ammunition stocks.

These depots would become the world's largest underground ammunition store. Soon after, the Ministry of Supply requisitioned Spring and Westwood quarries, not this time for ammunition, but for underground manufacturing of aircraft engines and gun components.

Before long underground spaces were high on the list of the War Department and all the remaining Bath stone quarries in North Wiltshire were requisitioned. However, five of them including the mighty Box, were unsuitable and were not used.

Work in the quarries stopped instantly, lamps and tools were left in place, with half cut blocks of stone still hanging from the cranes and saws still in their cuts. The quarrymen were laid off at a moment's notice.

The Royal Engineers moved in and started work at Tunnel, Monkton, Eastlays and Spring quarries. The access to the underground areas needed improvement and waste stone had to be cleared. The roads were laid in straight lines and covered with rolled asphalt.

Ceilings required considerable strengthening. Some bays were constructed as regularly shaped rooms by a massive underpinning operation. Elsewhere pillars were shaped as regularly as possible and the whole wall and ceiling surface was sprayed with a light coloured paint.

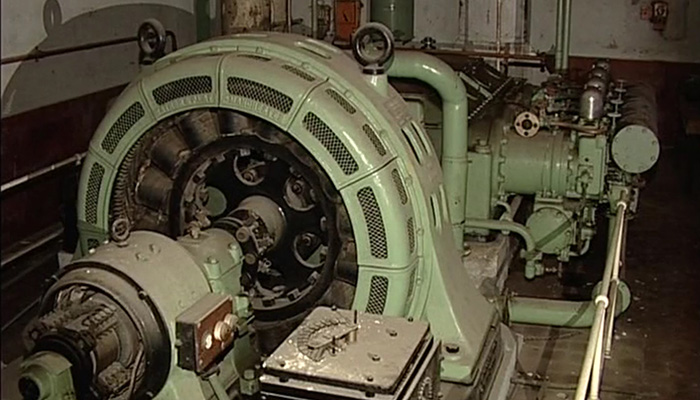

Various types of air conditioning were tried and expanded throughout the life of the establishments. They were all well provided with electric lighting and sewerage systems. Each complex had a large, standby, diesel-powered generating station. A very high standard of engineering was achieved throughout.

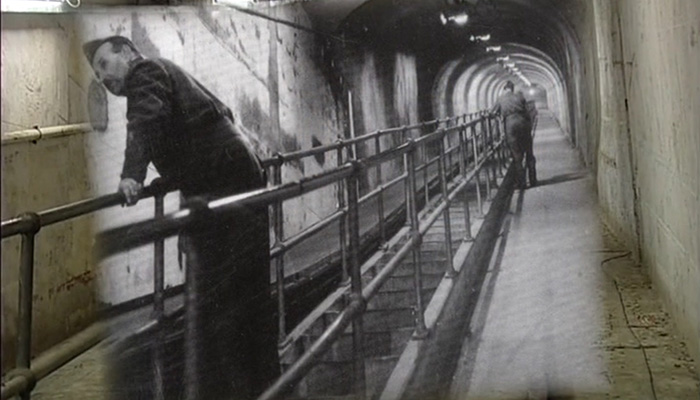

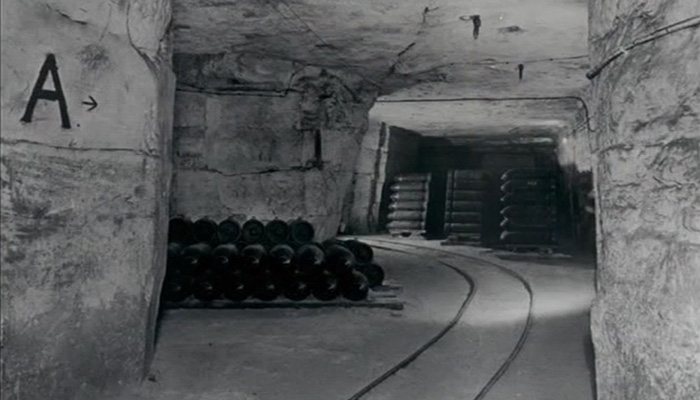

By this time, Tunnel Quarry was vast with its private railway leading into a purpose-built platform that allowed the stone to be loaded on to ten ton railway trucks. The ministry works enlarged and expanded this siding to incorporate a turning triangle. Trains were pulled into the depot by a War Department diesel locomotive. The locomotive would then run around its train using the underground tunnels and then propel the wagons into one of two sidings, seen here in the distance. All of these movements occurring underground were completely out of the sight of enemy bombers.

The original quarry workings had to be converted to take full-size railway wagons, and where necessary the passageways were enlarged and strengthened. Between the two sidings a platform area was built, this was to allow the loading and unloading of the ammunition from the trains at a rate of 2,000 tons a day. Each platform could accommodate a 30 wagon train and was over 660 feet long.

When the depot was fully operational in excess of 1,900 RAOC, Pioneer Core and civilians worked here.

Three Hudson Hunslet 0-4-0 diesel shunters were used in the depot and this siding to the right lead down to the locomotive engine shed.

The shed, complete with its own turntable, was equipped with an inspection bay and overhead crane. This enabled most repair and maintenance to be carried out. For major work, the locomotives were returned to the Royal Engineers depot at Bicester.

Re-railing devices seen here were used when derailments of the wagons occurred. The use of a normal lifting crane was of course out of the question.

During the conversion of the quarry and two-foot gauge railway was installed, this initially provided transportation of building materials around the huge site, but was later used for ammunition movement, using an overhead rope haulage system. In other areas of the depot the trucks were manhandled along the tracks.

On the northern edge of the site, a long drift passageway was constructed, which gave access to the ten five-acre ammunition storage areas adjacent. This drift is over 1,750 feet long.

The slope of the ground is clear to see here with the pulley wheel housing of the rope haulage device seen at the top of the drift.

With the coming of the Royal Engineers came mechanisation, suitably modified Samson coal cutting machines as used in coal mines elsewhere in the UK were put to work. Made by Mavor and Coulson of Glasgow, these caterpillar-tracked electrically-driven mechanical saws had a geared universal drive head carrying a large seven-foot-long chain saw. This could be raised, lowered, slued or rotated through 360 degrees.

The chain carried hardened steel cutters, which rapidly cut through the stone. This saw, still in use today at Monks Park Quarry, is one of the machines that was used in Tunnel Quarry in the 30s.

The history of quarrying evolved and manual cutting of the stone ceased. The vast scale of operations now being undertaken demanded mechanisation.

The Royal Engineers' works area, located elsewhere in the quarry, still has some of the trucks stored that were used on the Hudswell Drift, together with the only remaining complete Ruston diesel locomotive, no. WD1. A fleet of 28 of these locos was used during the conversion works of the quarry.

The depot is served by five slope shafts from the surface, on the left of the central steps the conveyor belt system once stood, and to the right a trolley winch system has now been installed. In this picture from 1943, the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) men check its operation, but we can only wonder what it must have been like back in those dark days of World War II.

This would have been a typical scene during that time. With the operatives manhandling the shells from one conveyor to another. The conveyor belt runs up hill from the slope shaft in what was originally the old quarry main haulage way. In quarrying days this would have been the route the stone would have taken down to the railway sidings.

Alongside the conveyor and throughout the storage area, the floor is covered with one-inch-thick colas spark-proof tarmac. You can see here the half-moon indentations caused by the ammunition handling.

Each of the five-acre ammunition storage districts was served by its own conveyor. Where the conveyor system ended, the shells were taken by sack barrow to their designated area.

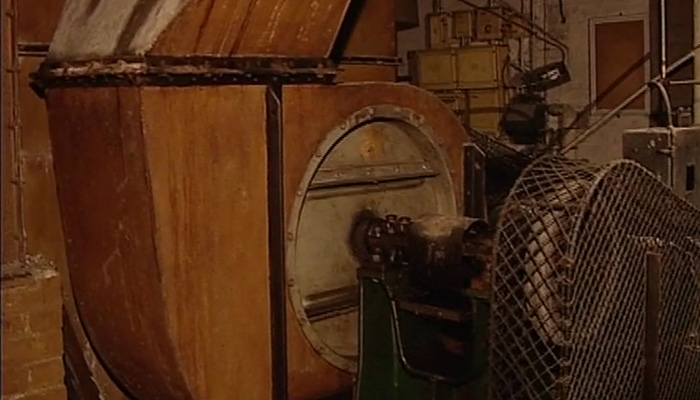

At the most westerly end of the quarry a large area was walled off, installed within it was a huge 160-inch, 400,000 cubic-foot per minute air screw fan. This propelled air around the ammunition districts by the air passageways and maintained the humidity levels. To reduce vibration it was mounted on a bed of four-inch-thick cork. The fan is still in use today.

In the main, this vast 44-acre site now lays disused, the Ministry of Defence still use a relatively small part of it for modern-day military purposes, because of this access is severely restricted.

Looking at these pictures today, it's difficult to appreciate that the two million tons of stone waste from the conversion work in Tunnel Quarry became the base for the new marshalling yards, here at Thingley Junction.

The sidings were completed in 1937 and a new west to south connecting railway line was added at the junction, becoming known as the Air Ministry Loop.

In this view, the tree line makes the course of its track bed. This connection allowed trains from the South of England docks to go directly into and away from Tunnel Quarry.

A Paddington to Bristol train passes the site of the old western junction of the triangle to the main line. The bridge extensions which allowed for the extra sidings and the pill box that defends them are all that remain today.

Further south at Beanacre, along side the Westbury-Chippenham railway line, more sidings were constructed. These were to serve Easlays and Rridge depots. This six-and-a-half-acre site closed after the war in 1948 and is now used by the national grid. Some of the original buildings survive today, albeit nearly derelict.

Ridge Quarry was re-opened by the military in the mid-30s, having laid empty since 1922. This No. 2 loading platform is all that remains on the surface today. Ridge closed in 1975, since when it has been used for agricultural purposes, but there is still evidence of its former use.

The black oblong shape on the rear wall is where the steam operated winch cable once ran from above the two railway lines embed in the floor. Outside the tracks converge before entering the now blocked slope shaft entrance.

This West Ridge incline dates from 1881 and was the original entrance into Ridge Quarry. It was re-opened in 1942 to allow access improvements to the lower level of the quarry.

However, the connecting passageway from the slope bottom to the new storage areas passed through treacherous ceiling formation. To ensure safety this area was subject to major support work with steel arches, brick reinforcement and concrete block work. The scrap men who dismantled these steel arches for cash certainly gambled with their lives in removing them.

With the War Office reoccupation of Ridge, they now required even more space than during the First World War. With control of the depot being given to the RAF, the floors were rolled and levelled and the two-foot-gauge railway system extended to cover all the storage areas. Ridge was capable of accommodating nearly 32,000 tons of ordnance.

As you travel around the site today, it's difficult to imagine the frenzied activities that took place here on the lead up to D-Day in 1944, when Ridge was dispatching over 14,500 tons of explosives a month.

All stacking and loading was carried out by 13 civilian gangers, employed by the RAOC.

A reminder of the dangerous conditions that now exist in these old quarries is this ceiling, which is laminated badly and has dropped. Tons of stones have trapped the old railways lines, making it impossible for even the scrap men to remove. The wooden telegraph pole that has snapped under the great weight has left the remainder of the ceiling sagging.

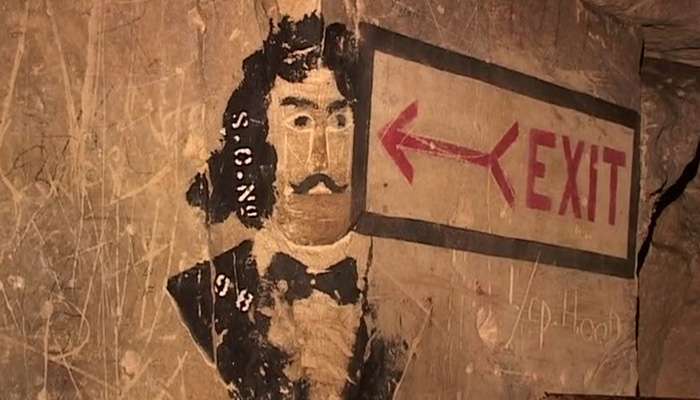

Old military signage and graffitis still exist. Ranging from this exit sign, to the bucket point No. 9 by the fire bucket rack, useful when explosives catch fire.

Storage locations signs, builders' markers and the ever-entertaining soldiers' graffiti still adorn the quarry walls. This smart Edwardian gentleman even has a three-dimensional nose carved in the stone.

A fine pencil drawing of the Queen Mary, with the artist perhaps wishing he was on it rather than being 90 foot underground stacking bombs. And, an image of a Spitfire by Henry Dunn of the RAOC.

Here's a large OXO cube container that was once used as someone's sandwich box. Carvings in the stone represent the local manor house, church and workers' cottages, leading to the quarry slope shaft and underground passageways. The original quarrymans' calculations can also be seen, with the DJ making his mark in 1901.

An old vertical ventilation shaft, seen here on the right, was adapted by having two electric lifts and wooden guides installed. This is all that's left today. The shaft having been filled in with old stone and earth, and the timber lift guides lying rotten and covered in fungi.

In the main slope shaft dual gauge railway tracks were fitted, so that the military two-foot-gauge and the quarry two-foot five-inch gauge trucks could both use it. The double railways tracks at the bottom of the shaft served as a reception and marshalling area.

The quarry is crossed by a major slip-fault in the stone, resulting in one half of the workings being some 20 to 30 foot lower than the other. Two sloping haulage ways were constructed to connect the upper and lower levels.

Railway track was installed down the slopes and the trucks were hauled and lowered by a winch.

Elsewhere in the depot, the trucks were manually handled. Because of the slip-fault, it was necessary for the ceiling to be substantially reinforced. Partial flooding occurs where water permeates through the fault line.

This room at the top of the slope housed one of the two compressed air driven winches.

Some months after stacking of ammunition had begun a construction program was initiated designed to produce a layout of storage areas more regular than the random patterns of existing pillars. The plan was to reinforce the stone pillars by corseting them with concrete, making them rectangular in section with straight haulage ways in between.

In early 1938 concreting began on 15 pillars in the South-Eastern corner of the quarry, but this work was suspended a few months later. The cost of the work and quantity of materials were much greater than anticipated and were out of all proportion to the benefits gained. The quarry now sports pillars in the various stages of corseting, showing the progress made before work was abandoned.

The steel reinforcing rods partially obscure the earlier quarrymans' picking marks, which would have been covered by concrete if the job had been finished. When finished the pillars looked like this, complete with concrete corbelling.

After the war Ridge was deemed unsuitable for the long-term storage of munitions, as no air conditioning had been installed. The site was emptied of all ammunition by 1949, with the MOD administering the site until 1975, when Ridge was sold back to its original owners, the Neston estates.

In addition to the conversion works at Tunnel and Ridge work was also carried out at Eastlays and Monkton Farleigh quarries. However, the conversion work at Monkton was a very different matter.

Located high on the hillside in the Avon Valley, Monkton was the result of over 200 years of quarrying under the hilltop. The many workings had run into each other and by the 1930s the hillside was riddled with a network of tunnels extending to over 300 acres.

In 1937 the Royal Engineers moved in and started the laborious task of removing the loose stone and laying it out on the surface. All but the strongest pillars were removed and replaced with new ones, whilst concrete was used to render the walls.

The ceilings were strengthened where necessary and a new, solid flat floor was laid. The whole mine was painted white. Conveyor belt systems were fitted to serve the entire site. Together with a narrow gauge railway system. Plus many thousands of light bulbs.

New surface loading buildings were also constructed. A huge generator, similar to the one at tunnel, was installed as a backup power supply. This allowed the ammunition store to operate independently. It took six years and over 7,000 people to convert the quarry. The conversion work is believed to have cost about £17 million over 60 years ago.

Because of the poor road access to Monkton, a mile and a quarter long tunnel was driven down the hillside to the old quarry stone yard sidings located at Farleigh Down. A conveyor belt system was installed with the ammunition travelling at the rate of 250 feet a minute.

Beneath the sidings the conveyors belt system ended and the ordnance would be loaded to small wagons that were pushed to the bottom of a 30-foot-deep slope shaft. At this point they were assisted up on to the railway platform by a tram creeper system.

Before the tunnel was built, an aerial ropeway system was used above ground, but due to the risk from enemy action was soon replaced with the underground connection seen here under construction.

Railway wagons were then loaded for onward transportation of the ammunition.

After the war, Monkton remained in the hands of the MOD until the 1970s. The site was partially cleared in the late-1980s, when the Monkton Farleigh complex was opened as a museum. Sadly the museum closed in 1990.

Passengers on today's speeding InterCity 125 trains will hardly notice the now derelict shed in amongst the trees. Sidings have existed on this site since 1881, when the tramway from the quarry brought stone for onward shipment by the Great Western Railway.

But, things move on and whilst we were filming this programme, the site was due for further development and the clearance gang moved in again. This time they not only removed the trees that had re-established themselves, but all the platform supports as well. For a while, it looked as if the site would be used as a recycling centre, but planning permission was refused and we understand that it will now be used for paddocks.

Underground Factories & Stores

Due to the constant threat of bombing the Second World War, it was decided that important manufacturing industries would be safer underground. Spring Quarry, lying to the South of Tunnel Quarry at Corsham was used by the Bristol Aircraft Company for aircraft engine production.

Spring offered over 90 acres of underground workings, divided into three major sections, each separated by geological faults.

The eastern end was used for the production of the Centaurus engine, which powered the Hawker Typhoon, Tempest and the Sea Fury aircraft. The southwest area produced aircraft gun turrets by Parnell Limited and gun barrels made by the BSA Company. The northwest area was allocated to Dowty Limited, who made aircraft undercarriage, but they never moved in and the area remained undeveloped.

Five large good lifts were constructed, this allowed the machinery needed to produce the engines to be taken in and out of the quarry. With a daily workforce of over 14,000 people, access to the factory area was served by two escalators requisitioned from London Underground, and four large passenger lifts.

The conversion works in the quarry were carried out in much the same manner as we've seen at the ammunition depots. Flat floors, white walls and concrete reinforcing.

With the vast number of staff working underground, five large canteens were constructed, there were able to server 6,000 people in one sitting. The chairman of Bristol Aircraft Company, Sir Reginald Verdon-Smith, was incensed at the dull decor in the factory and not wanting his employees to feel oppressed while working underground, he insisted that the canteens were brightened up by decorating the walls with murals.

These were painted by the professional artist Olga Lehmann and Gilbert Wood. They were applied with a spray gun using only the paint supplied to the aircraft factory. Duck-egg blue, red oxide and black.

Unfortunately we're unable to show you anymore of this fascinating site, which includes undisturbed parts of the original Spring Quarry. This is due to access restrictions through part of Spring Quarry, which is still a government classified restricted area.

The old areas remain unaltered since the quarrymen moved out in the 1930s, leaving in place these cranes which are now sealed up for the foreseeable future by concrete walls, protecting whatever other secrets are hidden behind them.

Two miles west of Bradford-on-Avon, Westwood Quarry consisted of two independent workings. A quarry tramway originally ran down the steep hillside to the Avoncliff viaduct, Kennet and Avon canal and the Great Western Railway.

Today Avoncliff station, on the Westbury to Bath line, draws many tourists to the area, with the canal navigation being a popular leisure activity.

Between the wars, the Agaric Mushroom Company cleared a large area of the quarry and about half of this area was converted for use by the Royal Enfield factory.

The 200,000 tons of waste stone that were removed from here were tipped over the top section of the old quarry tramway outside the entrance.

This wartime photograph shows the broad plateau formed on the hillside on which a vehicle park, offices and works canteen were built. This modern day view shows the small stone yard, which was the car park and the works canteen, which is now a motor repair shop.

During the war, the Royal Enfield factory produced anti-aircraft predictors. Three-quarters of the workforce were women and concern was raised about them being underground for extended periods, so excellent welfare facilities were provided.

This included regular free medical checkups and every week, compulsory ultraviolet sun ray treatment in a specially prepared underground room. The staple product of the Royal Enfield company had always been motorcycles, with tens of thousands being built for the military.

After the war, Royal Enfield, who were still occupying the Westwood underground factory, received several thousand bikes that were sent back for refurbishment. The motorcycles were stored in the damp, disused, Agaric mushroom area of Westwood Quarry awaiting overhaul. By the early-1960s, Japanese imports killed off the British motorcycle industry. Royal Enfield closed all its establishments in midlands and concentrated on production of the 700cc twin-cylinder Constellation motorcycle at Westwood.

We filmed these surviving examples of the Constellations near Bristol, the very first time three had been together in preservation. One of the machines was certainly manufactured in the Westwood Quarry, as the owner remembered taking it back underground for a warranty claim.

Royal Enfield finally closed in 1970, but a small part of the works was taken over by ex-Royal Enfield employees who continued to operate for a further 20 years, until 1990.

These are views of the Westwood Royal Enfield factory today, sadly decade and abandoned.

The plating baths, where the chrome plated parts for the bikes were finished. The spray booth turntables, which still operate, just waiting for that tank to be added.

The national grid switch room, which could black out parts of Wiltshire so that the engineering work undertaken during the war could continue at all times. And, the brand new ventilation fan, delivered, but never fitted, and the door to the drawing office.

The other half of Westwood Quarry has now returned to its former roll of stone extraction under Hanson's ownership. In the deserted part of the quarry, the drinking troughs for the horses are still full and the cart tracks in the floor look as if they were made only yesterday, instead of over a hundred years ago.

Although a common practice in France, Westwood is the only UK quarry with stone props to strengthen the ceiling. Elsewhere, they're made of wood.

In the old mushroom section of the quarry a large pile of horse manure still remains. The mushroom section is readily distinguishable by the white tide mark around the wall, indicating where the top of the mushroom trays used to be.

Advertisement ‐ Content Continues Below.

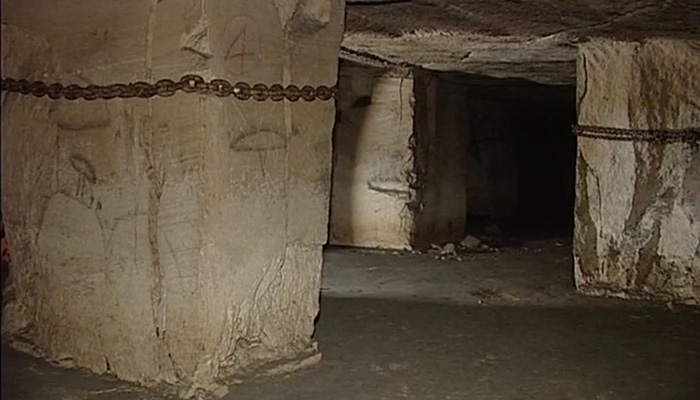

The chamber of horrors, so called because of a major earth movement that occurred one night in the 1930s, this caused incredible stress and lamination on the supporting pillars. Seen here is large chains put around the pillars to detect any further movement. None have been tightened since they were put on in 1935. This crane shows the enormous pressure that was exerted.

During World War II a separate isolated heading in the quarry, of about 25,000 square-feet, was converted and put to an even more important use.

Located down and off the main haulage way and served by its own specially installed railway, was a unique chamber. Protected by two set of vault doors, requisitioned from a bank in Bloomsbury in London, was an area that stored the nations treasures for the duration of World War II.

It soon became a fabulous national treasures safe house, housing artefacts from the Victoria & Albert and British museums, together with collections from the Bodleian Library, the Imperial War Museum and the Free French Museum of National Antiquities. The Rubens ceiling and Charles I's statue from Whitehall, and the bronze screen from the Henry VII chapel in Westminster stood alongside the treasures of all treasures, the Crown Jewels.

Queen Mary personally visited the quarry in 1943, just to see how the treasures were being cared for.

Considering the incalculable value of the treasures being stored here, security was modest, consisting of a keeper of one warder by day, and one warder and a Wiltshire police constable by night.

Whilst at Westwood the curator and staff made inscriptions on the stone walls in the lobby area to commemorate their stay in underground Wiltshire. One written by the keeper of Egyptian and Syrian antiquities, Mr C.J. Gadd, translates as follows: “year 1942 of our Lord God, year six of George King of lands, in that year everything precious, the works of all the craftsmen, which were sent out from palaces and temples, we brought down and stored in this cavern under the earth. A place of safety, an abode of quiet. So that they might not perish by fire and the strokes of an evil enemy.”

The museum staff, who were evacuated from London together with the precious works of art, continued their cataloguing and conservation work for the period of occupation. They were housed in the requisitioned Old Court Hotel, a rambling 18th century building, that was originally the Bradford Union Workhouse and was located alongside the canal at Avoncliff.

Temperature and humidity control within the chamber was of the utmost importance. The supply plant was capable of maintaining a temperature of exactly 65 degrees and a humidity of exactly 60%. Any deviation from these levels would ring warning alarms. The chamber was fed with correctly adjusted air through this ventilation system.

Men were employed whose sole job was to constantly inspect the walls for damp areas and re-treat them if required with damp-proof compound. The air conditioning system that was installed sits today out of use.

A special national grid electrical supply was connected to serve the chamber and there were switching arrangements so that towns within the locality could have their power switched off thereby maintaining a constant supply to the repository. Those residents of Wiltshire living in the surrounding areas sat in the dark on numerous occasions whilst the national treasures were kept warm and dry. In case of a complete failure of the national grid, a Crossley diesel engine generating set was available to supply power to the site.

One of the very first fire-smoke detector systems ever made which operated using a seven-point light ray system was installed within the storage area. This equipment was very technically advanced for its time.

We now move to the small group of quarries in the Hartham Park area. Pickwick Quarry was opened in 1899 by the Bath Stone Firms. This slope shaft was originally the entrance into Pickwick Quarry, but today it servers new quarrying areas to the north of the entrance.

Underground we connect to Travellers Rest Quarry, which is served by this vertical shaft. Note the upper-tear galleries from quarrying days. The dust in the air is from the extraction work nearby.

When the Royal Navy took over the two quarries in the 1940s, a connecting drift was blasted through to join the two together. A failed shot of black powder still hangs in the ceiling and some of the old lamp fittings are still in place.

A second vertical shaft in Travellers Rest was used for stone extraction between 1810 and 1850. Another slope shaft nearby, formerly known as the Hartham Park entrance, originally gave access to Copenacre Quarry. It was used for stone extraction up until the Ministry requisitioning in 1939. It was later used as an emergency exit from Copenacre, but is now out of use.

This long drift joined the slope shaft at Copenacre, but with the floor now being taken out by Hansons, the vista is changing rapidly. Pickwick, together with Brocklease Quarry at Neston, stored 10,000 tons of Royal Naval ammunition. The quarry veilings had to be strengthened and reinforced in many places to satisfy the requirements of the senior service.

The dunnage on which the ammunition boxes were stacked still remain on the floor. Marked out in true military fashion, the quarry walls sports come of the graffito as well.

At the far western end of the quarry a vertical shaft, known as the Helliger Lan shaft, gave direct access for the navy issues a receipts. The original railways lines are the only reminder today of its important use in the past.

In the wet areas of the quarry, the ceiling was lined with corrugated iron sheets to deflect the drips of water away from what was stored beneath.

What was it like in the navy days? These images may give you some idea.

The Ministry of Defence abandoned Pickwick and Travellers Rest in 1949 and they're now in private ownership.

During the run up to D-Day, all three depots, Tunnel, Monkton Farleigh and Eastlays issued 47,000 tons of high explosives from the quarries in just eight weeks. This was for the RAF bomber command's all-out offensive to gain air superiority prior to the D-Day landings.

Following the end of World War II and into the 1950s, the Cold War developed. With the threat of nuclear war, the government sought to establish more secure underground spaces throughout the United Kingdom.

If conflict were to occur this would allow the continued safe running of government. In time the government withdrew from many of the quarries and they were sold off, but some including Spring and Tunnel quarries remain secure military sites even to this day.

For years myths and stories have persisted about these quarries. These include tales of secret underground government war operation centres, the queen's royal bunker, prime minister's and cabinet office war rooms, massive communication hubs and a strategic store of ex-British railways steam locomotives.

It's not the intention of this film to go any further on these issues, as information about these areas is still security classified. Some day in the future, the withheld secrets on which these myths are bound will no doubt be revealed.

Anyone travelling on the main A4 trunk road through Corsham, cannot fail to notice the wartime buildings and modern offices of what was the Royal Navy storage depot, Copenacre.

In 1939 the navy had temporary stores of 10,000 tons of ammunition at Pickwick and Brocklease quarries, and electronic and optical stores at the small Bethal Quarry near Bradford-on-Avon. Following the heavy bombing of Coventry and Southampton during 1940, the Fleet Air Arm urgently needed safe underground stores.

Copenacre, a query of 19 acres, originally had two access shafts. A small but steeply graded Copenacre shaft near the main road that dropped down into the middle of the workings and the 1880 Hartham Park shaft, sited some distance from the quarry, access being via a long narrow drift. Adjacent to Copenacre was Pickwick Quarry, its entrance crossing over the Hartham Park drift.

The conversion works enlarged the Copenacre shaft and sank an additional new shaft nearby, as the Hartham Park entrance was deemed unsuitable because of its distance away from the main quarried area. Additional access was provided by two vertical lifts.

The site was official opened in July 1942, and on the insistence of the Admiralty, the surface buildings, in particular the tops of the lifts, stairwells and ventilations shafts had to have massive concrete protection from aerial bombardment.

This view is the site of the original Copenacre Quarry slope shaft entrance showing the widening that took place, so that the large goods lifts and stairwells could be accommodated. Down in the quarry, the two goods lifts shaft areas were substantially reinforced.

The lift cars were specially designed rail-mounted trucks with a horizontal loading platform. At quarry level the truck stopped in a pit ensuring the platform was flush with the floor. Two of these lifts were installed in the depot.

With the ensuing pace of the Cold War and the fact that a 100-foot-thick covering of solid stone offers substantially more protection from the new threat of the atomic bomb than anything on the surface, Copenacre was expanded in 1954.

Throughout its life, like many other subterranean sites, it suffered with the problem of water ingress. In places large areas of false ceiling had to be made to catch the dripping water and direct it to the drains.

This is one of the two passenger lifts that were installed. Here we're looking up one of the original vertical shafts of the quarry, the modern lift mechanisms cleverly engineered within it.

This passageway originally joined Copenacre with Travellers Rest Quarry, now walled off, it serves as a fresh air intake for Copenacre from a nearby vertical shaft.

The main haulage ways around the store are all named, with every pillar marked in the traditional military way.

By 1969 Copenacre was a self-contained unit dedicated solely to the storage, issue and testing of the entire range of electronic equipment for the navy.

Sizeable water tanks were installed to allow larger goods, such as torpedos, to be immerse tested before being dispatched. Large heated areas were also included to assist in drying items on receipt or after being tested. With 1,700 staff, it was the largest employer in North Wiltshire.

Following a series of underground fires elsewhere and an escape route was established out of Copenacre through to the Hartham Park slope shaft. The route was marked with reflective arches or torch positions, together with a control board. It consisted of a half-mile walk though the old quarry drift passageway, illuminated only by the occasional torch.

Following a government reorganisation, Copenacre closed in 1997.

These wooden buildings, which were subjected to dripping water from the quarry's ceiling, are covered by fungus, mildew and damp rot just a few months after the heating was turned off. Spreading fungus has quickly enveloped everything in its path.

Copenacre Quarry is today sealed, with all the access points bricked up, allowing only bats to have entry to the site. The Copenacre organisation also use stores areas in Spring and Monks Park quarries. Monks Park, having stood empty from requisition in 1941, was similarly converted to provide 10 acres of storage.

A new slope shaft with the same special horizontal loading platform and vertical twin passenger lifts was constructed. With the closure of Royal Navy Copenacre, the Monks Park site was sold off to Leafield Engineering, a defence company, who depose of redundant naval stores on behalf of the MOD.

Old Quarries Never Die

However, old quarries never die and those that didn't have their entrances sealed and spaces abandoned were put to other uses. An example of this is at Eastlays.

After its use as an ammunition depot and having been made surplus to MOD requirements in the mid-70s, Eastlay Quarry complex was acquired by Octavian Wine and was brought back into use.

This time instead of storing precious explosive for the country's existence, it was to store precious fluids for the country's enjoyment. Wine, wine and more wine. Gallons of it, in every shape and size of container you can imagine.

During its period as an ammunition storage complex, the large quantity of waste stone that had to be cleared from underground was tipped out on to the surface around the slope shafts. This created an artificial hill, which today is a nature reserve, but by searching through the 60 year tree growth, one can find the remains of the lookout post at the highest point where armed troops once stood guard over the important stores below.

The original quarry slope shaft was poorly situated as it emerged into the middle of the quarry, however it was used and we can see here the surviving railway tracks. The doors to underground are still in use today for ventilation and as an emergency exit.

The Ministry sank two new slope shafts, these are the ones that Octavian use. The surface loading bays were soon converted to accept modern day articulated lorries, instead of the 1940 Bedfords. The surface buildings only need minor alterations to cope with modern day loads. After all, boxes are boxes, whether they contain TNT or Chardonnay.

We now go underground using the No. 1 slope shaft that still sports the original 1940s wartime paint.

Underground changes were required to make it suitable for modern day use. The extensive conveyor built system had to be removed to allow a new era of battery trucks to roam freely. The web of railway tracks that wove their way round this vast 24 acre site were nearly all removed.

The special spark proof asphalt reminds modern day visitors of the tons of bombs and shells that were manhandled here in the past.

With Eastlays storing nearly 2,000 tons of high explosive bombs and 45,000 tons of TNT and cordite during the war, it was necessary as it was at Tunnel and Monkton Farleigh depots to have efficient air conditioning. Numerous dedicated air service tunnels were constructed with two mighty circulating fans built deep in the quarry.

An air washing chamber was added so that the temperature and humidity in the quarry could be and still is controlled accurately. Each storage district has its own window to allow the air to circulate.

Like other Ministry quarries, an independent generating powerhouse was incorporated. This power plant is a Blackstone-Brush eight cylinder diesel engine, driving a 350kVA Mather & Platt generator.

The quarry had a badly faulted roof, which required closely spaced steel girders in far greater quantities than at any of the other converted quarries.

Today, Octavian's operation at Eastlays handles over four million cases of wine a year and has on average 800,000 cases stored. The military connection with the modern day Eastlays has not been totally lost. Whilst filming we found a stock of Royal Navy rum, packed in 1955 and still awaiting distribution to one of her majesty's ships.

We've just seen the modern stacking methods used for the wine, but back in 1942 these 58lb boxes of TNT made by the Atlas Powder Company of the USA, all had to be stacked by hand.

As you travel around the complex, it's easy to see how tens of millions of pounds were spent on concrete and steel. For not only here, but at Tunnel, Spring and Monkton Farleigh, these dark and dusty quarries were transformed into more acceptable working environments.

The construction firms of William McAlpine, already masters in concrete work, and George Wimpey were awarded most of the War Office quarry contract work.

The old ammunition district offices now control the wine stock movements. The wartime configured numbering system still survives on the pillars. All the ammunition depots had unique location numbering, which helped with the logistical movements of the shells, TNT and bombs.

And just in case you'd forgotten and thought we were travelling around a modern day warehouse, by opening a door in the depot wall, we're firmly reminded of the quarry's original use, by stepping back into the Pictors monk's Bath stone quarry of 1881.

Today the only indication that the quarry was once used for ammunition storage is this sea mine, which stands as a marker in the depot car park and the now badly faded depot sign on the approach road.

Another quarry that's survives commercially without producing stone is Bethal Quarry, situated in Bradford-on-Avon. Home to the Oakfield Mushroom Company, the former Bath stone quarry now produces mushrooms on a large scale.

Requisitioned by the Ministry in 1941, from what was then the Agaric Mushroom Company, it was used for the storage of naval anti-aircraft parts, radio direction finding equipment and optical equipment during World War II.

Due to the instability of the ceiling in the quarry and the relatively shallow overburden above, the quarry was not suited for further military use, so it was handed back to the mushroom company at the end of the war.

The quarry entrance is a short distance from the main road and has a slightly inclined entrance, with the quarry floor on a gradually rising level throughout.

The military strengthening works are plane to see, but this must rate as one of the cleanest quarries around, as the growing areas are regularly cleaned and the whole site lime washed.

The chug holes for the long gone cranes still reminds us of the quarry's origins. With this anchored pulley, which is slowly disappearing under the many applications of lime.

Modern Day Bath Stone

So, we've seen how the passage of time and two world wars have changed they way Bath stone is quarried. Let's just remember that pre-war the stone was removed manually. When the Royal Engineers converted the quarries for ammunition use, they introduced mechanisation, let's go and see how it's done today.

Here at the Bath Stone Group's Limpley Stoke Quarry, three mechanised saw operate every day. The heavy-duty large chain saws that cut the stone face are a far cry from the jadding bad and handsaws that were used in the past.

With the increased noise and dust levels in the inclosed heading space, personal protection for the quarrymen is essential. Unlike the old fashioned backfilled made up of small broken waste stone, part of the modern waste is dust and lots of it.

Here a prepared cut heading is awaiting the next stage, removal of the blocks. The quarryman inserts plugs and feathers to the sawn gap and with the aid of a pneumatic drill forces the feathers into the gap between the stone until the back face of the block sheers away from the heading and drops clear. It's then removed with a forklift truck. This six ton block is taken to the surface stone yard.

With what is known as the wrist block removed, the quarryman drills two holes down the rear face of the next block and repeated the procedure with the plugs and feathers, thereby allowing its removal.

Today's quarryman work as teams and are paid for the tonnage produced, just like the early days. Bonus schemes are common, with the mine manager taking the entire workforce to the pub for an evening's celebration when the monthly tonnage figure is exceeded.

With the next block now removed, we move to the underground sawmill. Any blocks that need trimming are taken here and dealt with before going to the surface.

The military bricks here in Limpley Stoke Quarry remind us of its TNT storage use, but the since then the original floor below the brick line has been removed and sold.

The role of the horses has been taken by the diesel engines, with a block of stone being removed up this main haulage way, on average every 30 minutes.

With every block weighted and marked, the stone is then stacked in the yard awaiting onward transportation.

At Monks Park the 1930s Samson's big brother the Dreadnought is seen in use. Of coal industry design, it allows quick and efficient cutting of the stone to take place. There's no spares department for these machines nowadays. If something breaks, then a new part has to be manufactured for it, but being reliable beasts defects are few and far between.

At Monks Park, quarried by Hansons, they're creating extremely large chambers by removing the base bed stone. Here a quarryman is stitch drilling the stone from above in preparation to removing it.

This is the modern quarry a horse.

Two quarrymen pass an old broken stacking crane that has been discarded, in what was a stone stacking area. And this is modern day backfill, not so neat and tidy as we've seen in the older quarries, but that's progress.

The quarry rails on the right are now out of use and are awaiting removal, as quarry trains are no longer used here due to health and safety considerations. The redundant 1958-built battery-electric locomotive is waiting to be relocated elsewhere.

However the original rails that were laid in the slope shaft are still in use today, as this remains the best method of transporting the stone up to the surface. With the slack in the wire rope taken up, the block makes its way slowly up the shaft. When the tuck leaves the horizontal, the Warrick Gate arm lowers, this is to stop the truck and its load from running backwards into the quarry in the event of the winch cable breaking. The gate's position is indicated in the winch room.

This barred window was the opening for original steam-powered winch cable, which was replaced by the electric version by the Ministry in 1952. The use of the winch today is controlled by an electric bell signal. Introduced in the early-1940s, this control system has changed little since then.

The slope shaft was the original 1881 entrance to Monks Park Quarry, which was previously known as Sumsions Monks. It was however refurbished in the mid-1950s, when the Royal Naval storage area at Monks Park was developed.

Approximately ten miles from the city of Salisbury is Chilmark Quarry. Chilmark is a good example of both high-tech and the historic. Here they have the most modern type of stone saw, but also a surviving operating quarry railway system. Located next to the old underground military complex, which was used for ammunition storage, a small limestone quarry has re-established itself.

The stone for both the original building of and recent refurbishment of Salisbury cathedral came from here. The quarry is small in comparison to the ones we've seen at Corsham, with this main haulage way leading down to the underground sawmill.

The limestone that's quarried here is harder than the normal Bath stone, having its own distinctive colour. At the end of the haulage way, there are two small store areas, and like Limpley Stoke Quarry, the base bed is being removed, doubling the height of the headings.

The quarry was used by the military until total closure in the 1990s and their signs can still be seen in the quarry. Proving that there is still some skill and care being taken building work, this is a very nicely constructed emergency exit for the quarry.

The latest technology can be found here, with this brand new forklift-mount hydraulic saw. A millennium version of the 1930s Samson. Because of the limestone, the saw has to work a lot harder. This was its first day in service and the operators were familiarising themselves with it.

The quarry is unique as it has the only underground quarry railway remaining in operation. Two of the original ammunition depot trucks have been retained for moving the stone from the quarry to the stone yard. The locomotive is a Simplex diesel made by Motor Rail Limited of Bedford.

There's a gradient out the quarry, so careful application of power is needed to haul the heavy load. At this point it passes over the now disused military camp road, which gave access to the proving sheds, where the ammunition was checked on entrance and exit to the site.

For a short distance the train run parallel to the Fovant to Chilmark road, before crossing the road into the stone yard. The stone yard is above the now empty military storage quarry. Blocks in the foreground are awaiting dispatch, while the large stones on the left are stored here before cutting.

Bath stone, rightly, holds a place of fame amongst the leading English building stones. This early picture of a stonemason's workshop shows little has changed over the years. The main change has been mechanisation, as this view of the Bath Stone Group's Yeovil yard shows. The overhead crane allows the stone to be easily moved around the yard.

Once brought to the yard, the quarried block is given a primary cut by this multi-bladed bench saw. The six diamond tipped blades are seen here cutting a six ton block. The saw bench is 30 years old and still gives reliable service.

The secondary cuts are then made using a six foot circular saw, again diamond tipped teeth make short work of sectioning the stone to its required size.

For the more intricate stone work an Italian beaded diamond wire cutting machine has brought computers into the stonemason's yard. Using state-of-the-art software, it's capable of cutting the stone into the many varied shapes required by today's architects.

The yard handles over 1,000 cubic feet of stone each week. This contributes to over 50% of the stone requirement in the marketplace.

Another use of Bath stone has been the manufacture of extremely high quality and uniquely designed fireplaces by the Rudloe Stone Company. Situated near Box village, and using locally acquired crushed Bath stone, they produced cast stone fireplaces by using a moulding technique with dyes and colourants.

One style is based on the stunning Western portal of Brunel's Box Tunnel, surely complementing any living room.

Traditional stone carving still survives, thanks to establishments like Shute Farm in Downhead near Shepton Mallet. The old farm has been converted into the Shute Farm Studio. Tutors at the school are professional artists providing excellent teaching and guidance.

The studio offers talented artists the opportunity to share their technical knowledge and expertise in a supportive environment. People from all walks of life are given the opportunity to travel the road of discovery, learn new skills and improve their existing abilities, and perhaps gain a great knowledge of creativity.

There's no getting away from the War Department, even here, with this old tool sharpening stone standing outside the workshop. For the more adventurous students, larger projects are undertaken in the studio grounds.

Back at Hazelbury, one of the early-19th century quarry entrances can just be seen beneath the deposits of time. The site sees a different use today, with 21st century pastime pursuits, but some traditional activities remain.

Could this girl out riding be a descendent of be a long lost relative of St. Aldhelm, trying to recover his thrown down gauntlet?

The architectural heritage of the city of Bath, built out of Ralph Allen's Combe Down oolite, servers as a monument to the skill and craftsmanship of the quarrymen, who in the golden days of Bath stone, made Britain the world leaders.

But, it's not just the Bath stone buildings that hold an important place in the history books, we shouldn't forget that the quarries are themselves a living testament to the changing fortunes of this country as a whole.

Two world wars, the Great Depression and the invention of modern building materials, such as concrete, all left their scars on the industry. The ceasure of virtually every quarry in the area by the War Office certainly made a last impact that can still be seen.

Today there's a serious threat that this history will be lost forever, old quarries are in danger of being sealed and forgotten. This programme brings to the viewer sights that have seldom been seen and some that may never be seen again.

Today, due to the dangerous conditions that prevail in most of the old quarry workings, access is prohibited to all but a few. We must thank the Ministry of Defence, the mine managers and owners, and above all today's quarrymen, who still have tremendous pride in the job that they do to keep the golden Bath stone alive.

Without their cooperation it wouldn't have been possible to make this programme and some great moments in the history of this important industry would have slipped by unrecorded.

What future generation chose to do with the Bath stone industry's vast honeycombed areas of Wiltshire and Somerset remains to be seen.

So, there you have it. The story of 2,000 years of Bath stone quarrying. The world heritage city of Bath still has a need for Bath stone, so its history continues to be written.

From Pulteney Bridge in Bath city centre, goodbye.

Credits

Narrated by: Jeremy English

Camera: James Manday, Brain Williams

Sound assistant: Celia Menday

Technical advisors: Walter Steele, Keith Palmer, David Palmer, Dan Winquern

Script associates: Nick McCamley, Derek Hawkins, Keith Palmer, David Palmer, James Menday

Script supervisor & production: Eileen Franklyn

Specialised lighting equipment: Jon Duxon, Graham Barry

Sound editor: Tom Scotford

Sound post production: Mike Gooden

Music: Trackline Music Services

Preview consultants: PlanetERF, Ann Scotford

Original programme concept: James Menday, Walter Steele

The producer wishes to thank: Chris Batstone, Martin Bishop, Tony Comer, Peter Crompton, Roy Francis, Margaret Hill, Steven Menday, Joe Price, Gordon Tucker, Vic Turk, John Turner, Andy Ward, The Bath Film Office, The Bat at Work Museum, The Bath Stone Group, Chilmark Stone Ltd, Crisp Cowley, Hanson Aggeregates, Joint Support Corsham, Longleat House, Oakfield Farm Products, Octavian Wine, Prior Park College, The Quarrymans Arms, Rudloe Stone Works, Roman baths Museum, Shute Farm Studio, Royal Enfield Owners' Club, Wansdye Security, and the many individuals whose contributions were invaluable to the making of the programme.

Archive photography supplied by: Nick McCamley, Derek Hawkings, Bath at Work Museum, David Pollard, Eddie Menday, Colin Maggs MBE, Imperial War Museum

Produced and edited by: MVP Video Services, Guildford

Want More Underground Secrets?

UndergroundJanuary 12, 2019

'Lifting The Lid On Box Hill'

Further Reading

Dive into the world of the paranormal and unexplained with books by Higgypop creator and writer Steve Higgins.

Hidden, Forbidden & Off-Limits

A journey through Britain's underground spaces, from nuclear bunkers to secret wartime sites.

Buy Now

Encounters

A historical overview of UFO sightings and encounters, from 1947 to modern government reports.

Buy NowMore Like This

UnexplainedAugust 31, 2024

Top Skywatching Spots In Wiltshire To Witness The Warminster Thing

ParanormalAugust 27, 2024

Joining The Warminster UFO Skywatchers For A Night On Cradle Hill

ParanormalAugust 16, 2024

Revisiting The Warminster UFO "Thing"

ParanormalAugust 11, 2024

A Trip To Wiltshire's Crop Circles To Meet The People Who Believe In Them

See More on Audible

See More on Audible

Comments

Want To Join The Conversation?

Sign in or create an account to leave a comment.

Sign In

Create Account

Account Settings

Be the first to comment.