A Visual Guide To Steve Higgins' Book 'Hidden, Forbidden & Off-Limits'

By Steve Higgins

March 21, 2023

March 21, 2023

This page is more than two years old and was last updated in February 2024.

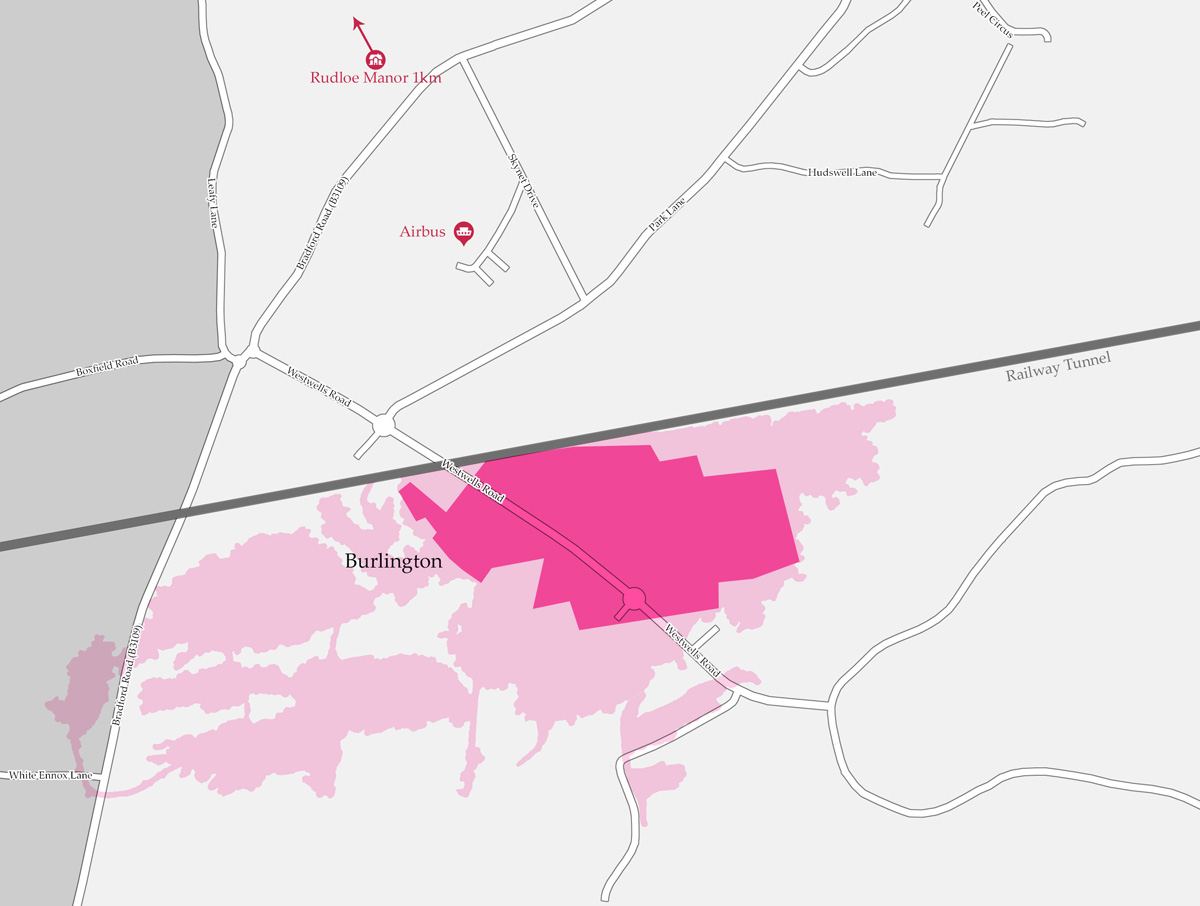

My recently release book 'Hidden, Forbidden & Off-Limits' includes several photos and maps of the underground bunkers and tunnels I refer to in the book.

The book, which is available from Amazon now, isn't a picture book. It's primarily text, so the photos and maps are only printed in black and white. So, I thought it would be nice to expand on the 20 photographs included in the book and share them in full colour.

This may be especially useful if you purchased the audio version of the book through Audible, in which case this page should server as a companion and visual guide to the audio.

Buried Treasure

A photo taken in 2022 of Box Tunnel, which runs beneath Corsham and right through the heart of the underground military tunnels.

The story of 'Hidden, Forbidden & Off-Limits' in many ways owes its origin to this tunnel, which was constructed in 1838 by the legendary Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

The tunnel might have made commuting to London from the west country easier, but its construction also had a huge impact on the local stone industry. While digging the tunnel, Brunel's workforce discovered huge quantities of Bath Stone.

Following the completion of the tunnel, many stone quarries opened in the area to extract the stone, which further expended the warren of tunnels that the Ministry of Defence use to this day.

The story of 'Hidden, Forbidden & Off-Limits' in many ways owes its origin to this tunnel, which was constructed in 1838 by the legendary Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

The tunnel might have made commuting to London from the west country easier, but its construction also had a huge impact on the local stone industry. While digging the tunnel, Brunel's workforce discovered huge quantities of Bath Stone.

Following the completion of the tunnel, many stone quarries opened in the area to extract the stone, which further expended the warren of tunnels that the Ministry of Defence use to this day.

Where The War Was Stored

My first underground trip and the one that got me hooked, was to Monkton Farleigh Mine. This photo of what awaited us at the bottom of the slope shaft in District 20 was taken in 2002.

Monkton Farleigh Mine was part of the vast network of underground tunnels left by Bath Stone quarrying and had been converted into an ammunition depot as part of the war effort. The underground landscape we were standing in was the result of extensive conversion that was carried out at Monkton Farleigh, allowing it to hold up to 120,000 tons of ammunition.

Monkton Farleigh Mine was part of the vast network of underground tunnels left by Bath Stone quarrying and had been converted into an ammunition depot as part of the war effort. The underground landscape we were standing in was the result of extensive conversion that was carried out at Monkton Farleigh, allowing it to hold up to 120,000 tons of ammunition.

A photograph of me exploring Monkton Farleigh, something that I did regularly for a few months after discovering the abandoned ammunition depot in 2002.

We spent many of our days off trying to get a sense of the size and layout of the bunker. We discovered hundreds of numbered storage bays, passed through countless metal blast doors, and peeked into several underground offices. We also explored switch rooms and conveyor control rooms and found the many huge fans that once circulated air around the ammo store.

We spent many of our days off trying to get a sense of the size and layout of the bunker. We discovered hundreds of numbered storage bays, passed through countless metal blast doors, and peeked into several underground offices. We also explored switch rooms and conveyor control rooms and found the many huge fans that once circulated air around the ammo store.

In July 2002, just three months after we discovered Monkton Farleigh Mine, its owner bricked up the entrance and a "private property" sign had been painted on the wall. Normally, I'd say that a no-entry sign does little to deter urban explorers, but in this case, the tunnels were well and truly sealed.

Despite being walled up, there was plenty more to see in the area. Monkton Farleigh Mine was served by a tunnel that surfaced in some railway sidings almost a mile away.

Having been permanently locked out of the ammunition depot, it was exciting to get the chance to be heading underground again, and like our first trip into Monkton Farleigh, we had no idea what to expect underground at the Farleigh Down sidings.

Having been permanently locked out of the ammunition depot, it was exciting to get the chance to be heading underground again, and like our first trip into Monkton Farleigh, we had no idea what to expect underground at the Farleigh Down sidings.

Browns Folly Mine can also be found under the village of Monkton Farleigh, but is separated from the former ammunition depot by a blast-proof perimeter wall.

These old stone workings are packed full of features and clues to their time as a working stone mine. Perhaps the most memorable feature is a small, naturally filling square reservoir, which is always full of clear, blue water.

These old stone workings are packed full of features and clues to their time as a working stone mine. Perhaps the most memorable feature is a small, naturally filling square reservoir, which is always full of clear, blue water.

The Extraterrestrial Connection

The infamous mound protecting one of the entrances to the underground tunnel complex beneath MOD Corsham, a location that was made famous by UFO enthusiasts in the 1990s. It's easy to see this entrance through the MOD's fence from Westwells Road. If you know what you're looking for, you can also spot some more modern buildings housing lifts and various slope shafts leading into the ground.

Photo: Derek Hawkins

MOD Corsham was formerly known as RAF Rudloe Manor. This is an archive photograph of the manor from which the site got its name.

In 1940, the manor house was bought by the Air Ministry, a government department that oversaw the RAF. It housed the headquarters of the No. 10 Group, which was part of the RAF Fighter Command and provided defence for the south-west of England and South Wales.

In 1940, the manor house was bought by the Air Ministry, a government department that oversaw the RAF. It housed the headquarters of the No. 10 Group, which was part of the RAF Fighter Command and provided defence for the south-west of England and South Wales.

World's Biggest Underground Factory

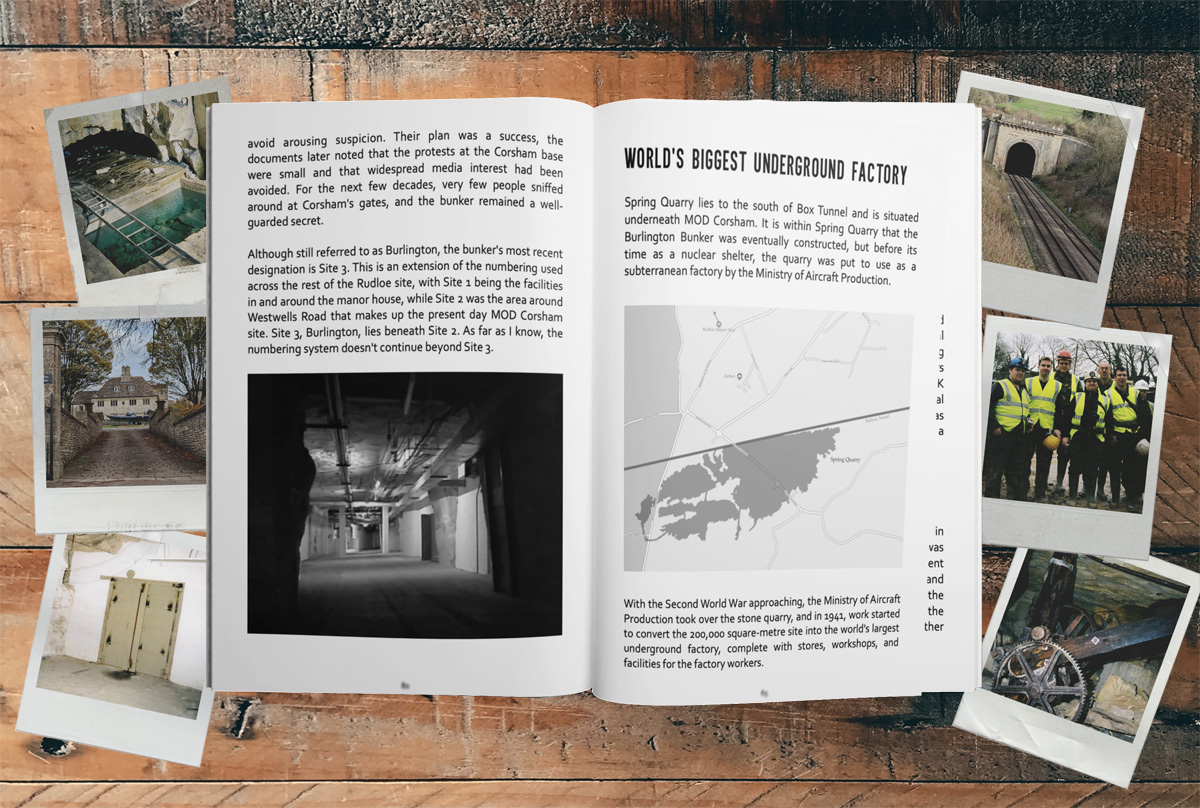

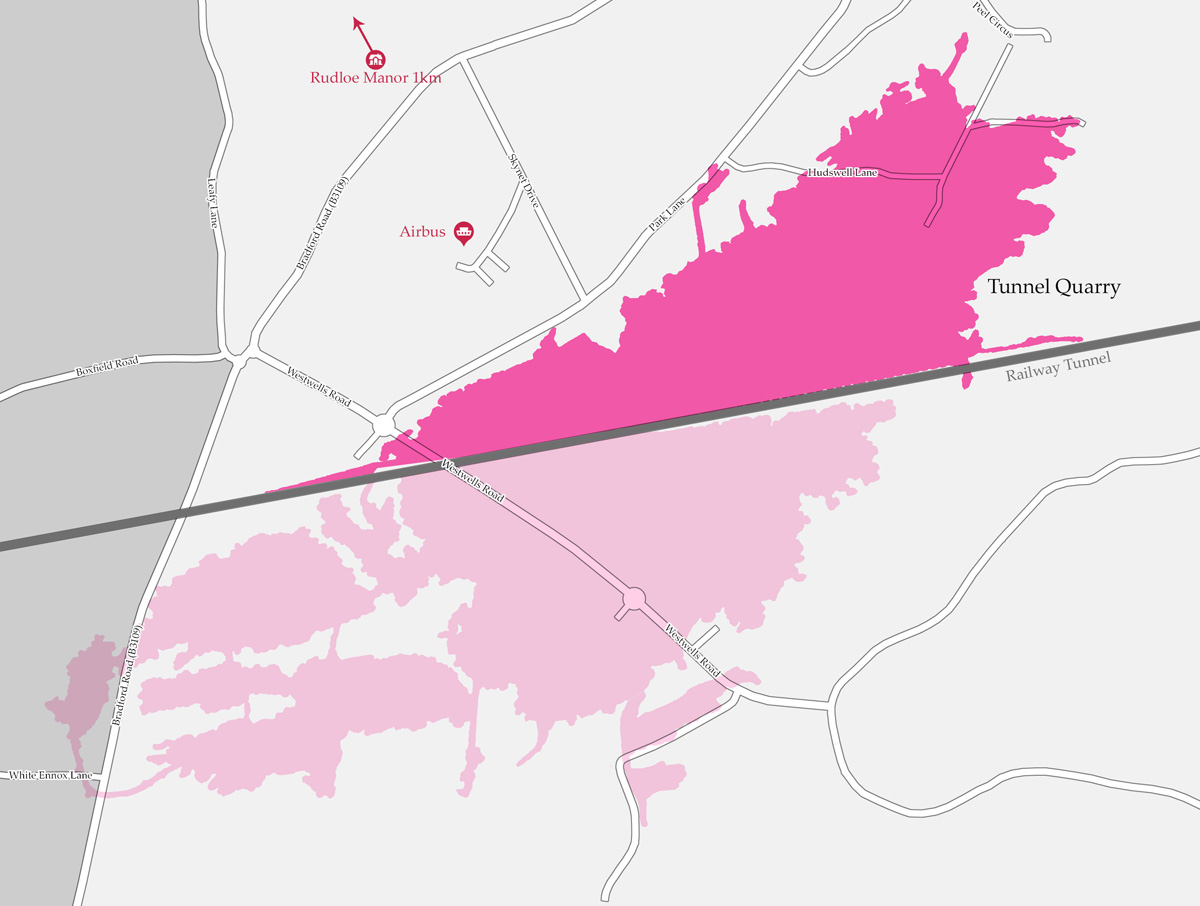

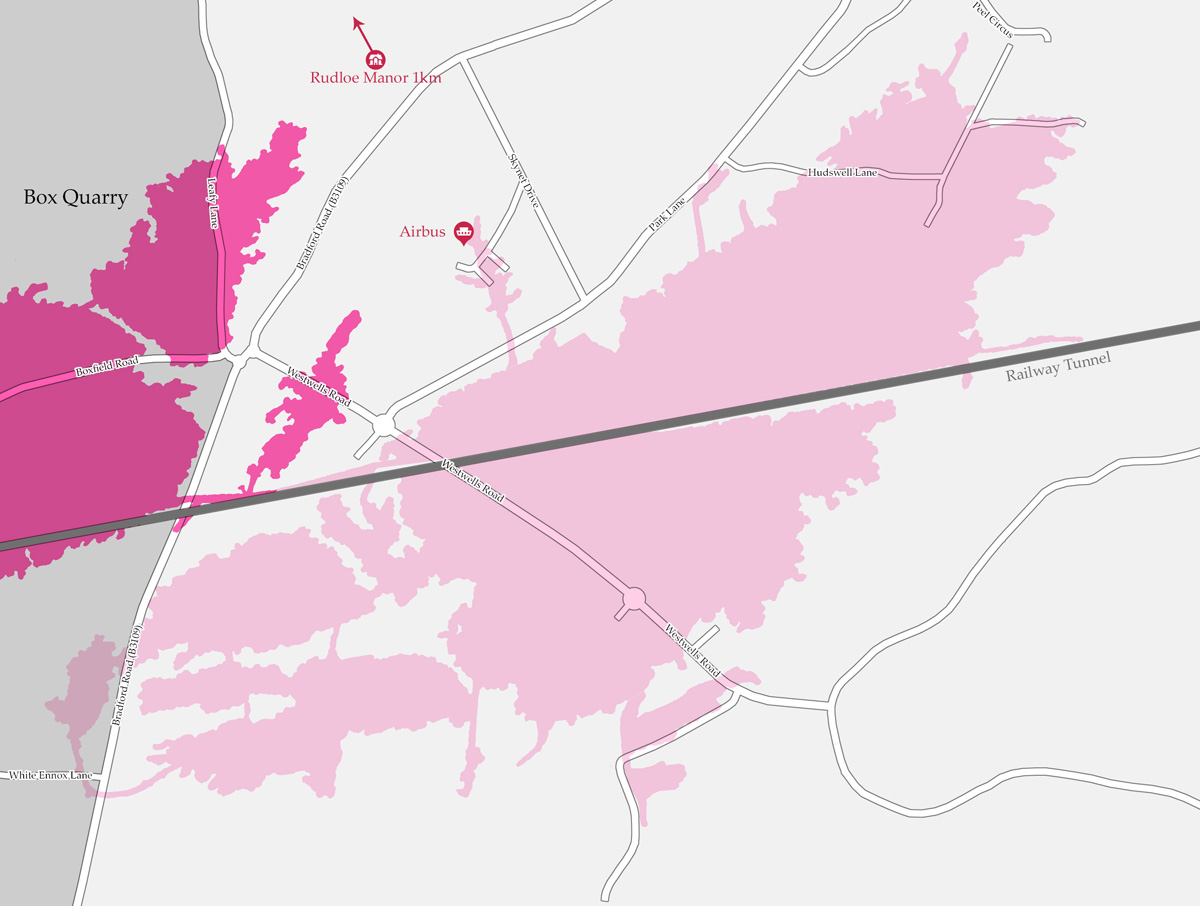

The first map I included shows the rough location of Spring Quarry, which lies to the south of Box Tunnel and is situated underneath MOD Corsham. In wartime Britain, the quarry was put to use as a subterranean factory by the Ministry of Aircraft Production.

This photograph shows one of the underground blast doors found in Spring Quarry.

A photograph of a small brick building on White Ennox Lane. Inside this innocuous building on a normal-looking country lane is a metal stairwell that spirals 30 metres down into the quarry. The stairs were a designated emergency exit from the aircraft factory, and the shaft also provided an access point for services such as gas and electricity.

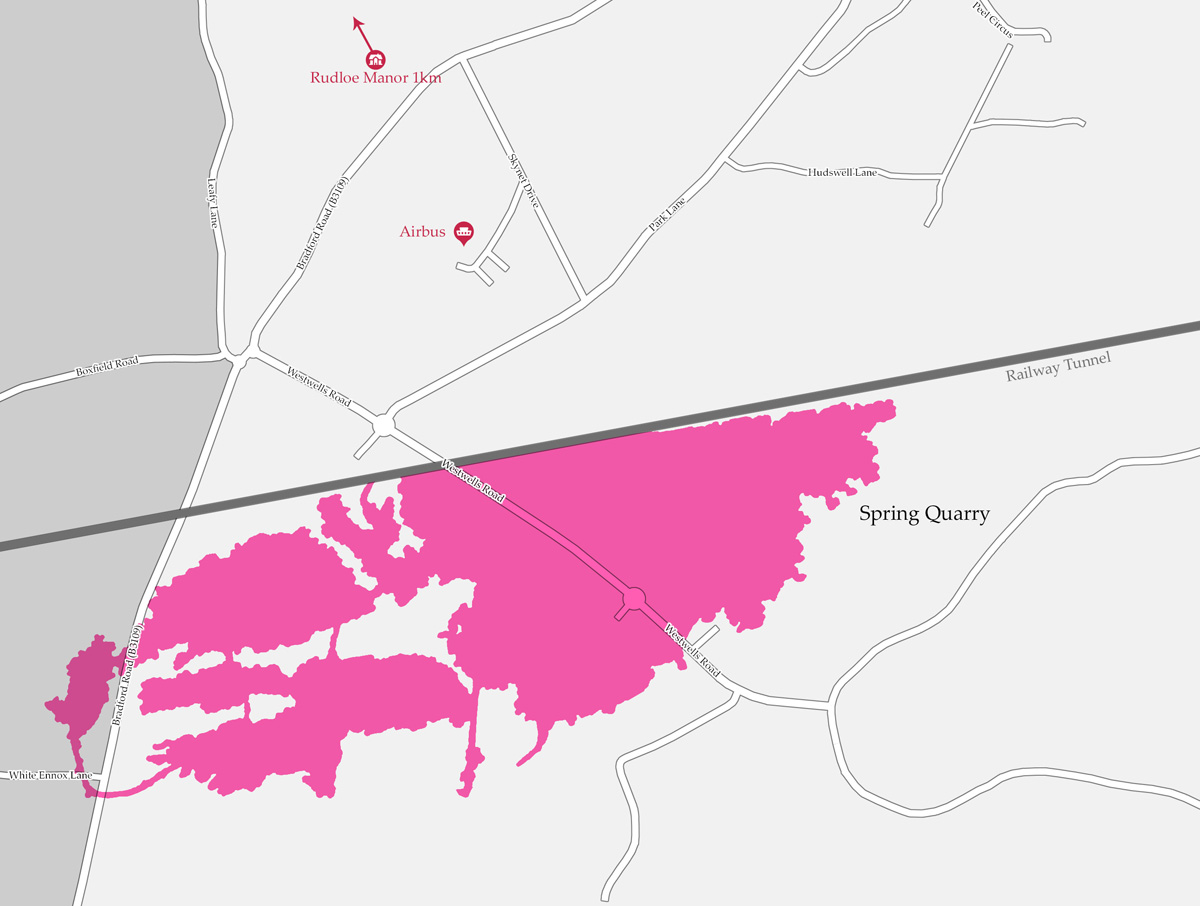

The next map shows Sands Quarry relative to Spring Quarry. This former stone mine was used as an emergency escape route from the underground factory. Reflective metal checkpoints were installed to guide factory workers from Spring Quarry to the surface slope shaft of Sands Quarry. These checkpoints would have been lit only by torchlight.

Burlington Bunker

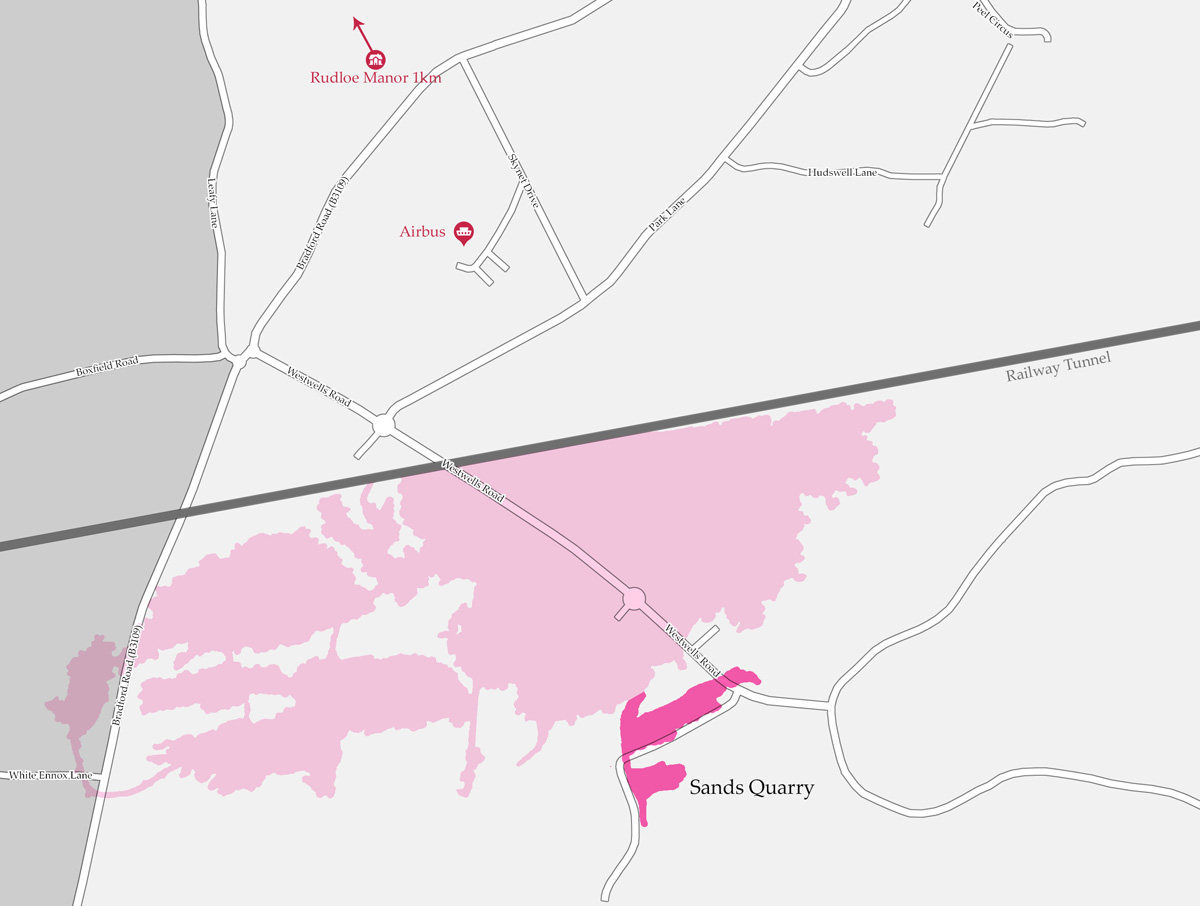

This map shows the size and placement of Burlington Bunker within Spring Quarry. Burlington is often described as the holy grail of urban exploration, and its origins are rooted in the Cold War. Although conspiracy theorists have pestered the MOD for information and urban explorers have pushed their limits trying to get into the bunker, few members of the public have ever seen inside.

This low-quality image is actually a still taken from some video I shot in Burlington. It was a little unfortunate that at the time of my visit, affordable camera technology wasn't what it is now. I filmed much of my visit using a camcorder, which wasn't even HD, let alone 4K. Compared to modern cameras, it was pretty low quality and didn't do the trip justice. Looking back, it was a mistake to focus on video rather than taking photographs, but even my compact still camera probably wasn't fit for purpose.

The Trident Link

Spring Quarry, which contains Burlington, sits to the south of Brunel's railway tunnel. This map shows the location of Tunnel Quarry to the north. In some ways, Tunnel Quarry should be more interesting to urban explorers as it houses more present-day secrets, but the reason why the curious aren't scrambling to find a way to get in is because it is not as well known as Burlington.

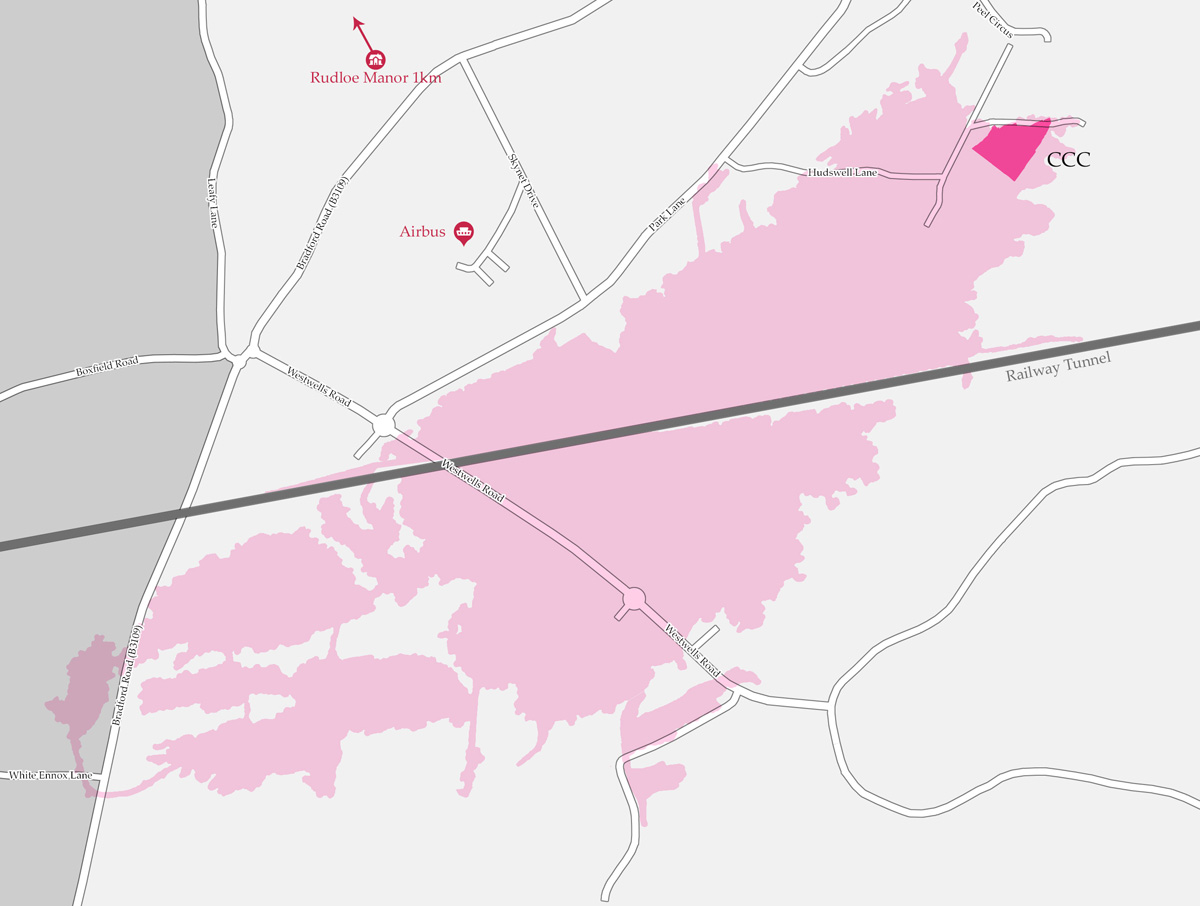

This map shows the location of the Corsham Computer Centre (CCC) within Tunnel Quarry. Due to its active status, little is known about the command bunker, and the MOD's official line is that CCC is a data processing centre. CCC is so secretive that it was never even approved by or even discussed in parliament until two decades after its creation.

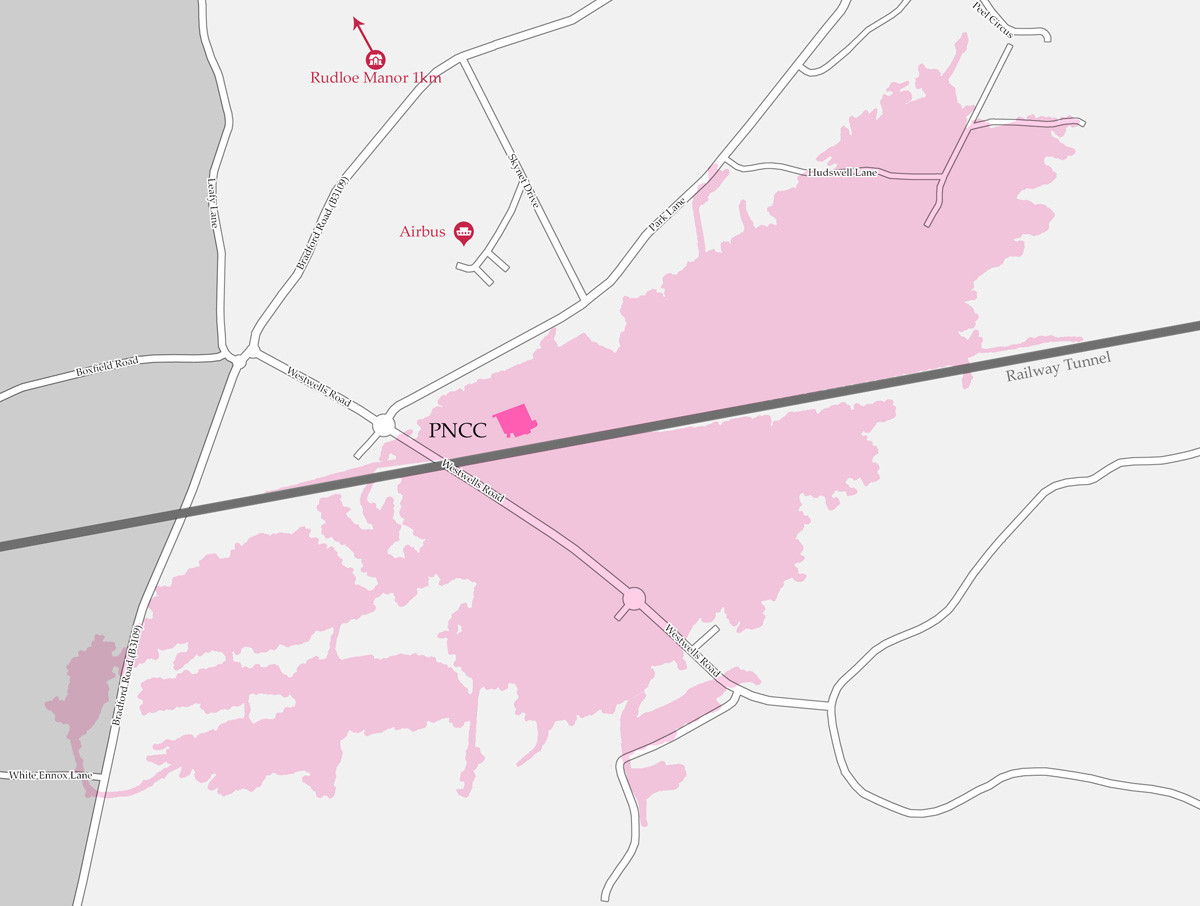

At the other end of Tunnel Quarry is an area known as the Primary Network Control Centre (PNCC). It is contained within a 3,000-square-metre area that started out its military life as the home of the South West Control, a communications centre serving the south-west of England. It housed communications switching equipment, telephone switch boards, and teleprinter equipment. It was later that the site became known as PNCC until it closed in the 1990s.

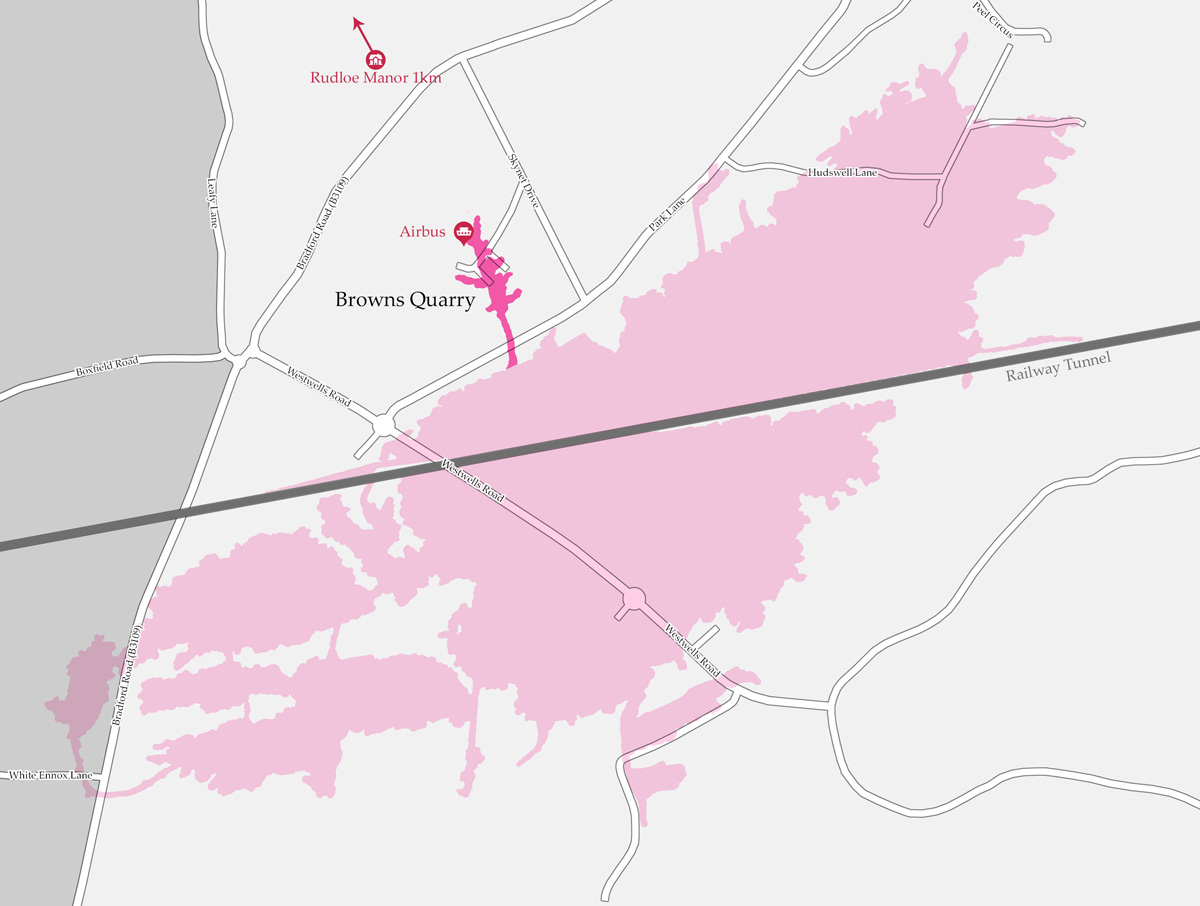

As shown in this map, to the north of Tunnel Quarry is Browns Quarry, which was converted by the RAF in to an underground operations room.

Going Underground

This map shows where the MOD tunnels meet Box Quarry, which is by far the biggest and most complex of all the remaining Bath Stone mines. It is in fact the largest stone mine in the country, with many miles of interconnecting passages. The quarry is located at the western end of the MOD's Tunnel Quarry site and is partly owned by the MOD but after some modifications, it was only used as an air inlet for the Tunnel Quarry complex.

This photograph taken on one of my visits to Box Quarry shows how the abandoned stone mine exists as a fascinating time capsule, a snapshot of the quarrying days. The large wooden cranes used to haul stone around are still in place, the imprint of horses' hoofs can still be seen in the quarry floor, and there are piles of cut stone that never made it to the surface.

This is the entrance to Ridge Quarry, where at one point in time determined urban explorers have managed to prise one of these moss-covered stones away from the opening to reveal a gap that is just big enough to squeeze through. It used to be possible to carefully drop down on the other side, and you'd find yourself standing at the top of the slope shaft on the first of about 150 steps leading down into the former quarry, which later in life was converted into an ammunition depot.

Liquid Assets

A photo of me and some of my exploration buddies taken at Hartham Park Quarry in 2006 before we were shown around the stone quarry by the legendary quarry owner, the late David Pollard.

The tour gave us a chance to see some modern methods of stone extraction. The tools of the trade are beasts, the most terrifying of which is a two-metre-long heavy-duty chainsaw. It's mounted on a hydraulic head that can be raised, lowered, and swung around in pretty much any direction. The whole thing towers over its human operator and moves around the workings on its own caterpillar tracks. These electrically driven saws cut through the stone like a knife through butter, and surprisingly, they're relatively quiet.

From Hartham Park, we were taken through into the adjoining Copenacre Quarry, a former Royal Naval depot that provided support for the Navy's electronic equipment with storage and testing facilities. The tunnel we were walking through was constructed as an emergency escape route for Navy staff working below ground.

My underground adventures continued when I moved to the nation's capital. This photo was taken in 2010 inside Paddock, a former government bunker located beneath the residential homes in Dollis Hill. I visited the subterranean hideout as part of a London Open House event, which sees iconic buildings across the capital open their doors to the public for free each year. The open day at Paddock was hosted by Subterranea Britannica, an excellent society formed in 1974 to research and explore man-made and man-used underground places.

The Holy Grail

Myself and my seven friends were invited on the tour of Burlington Bunker in 2008. This photo shows me in the huge, wooden telephone exchange, where banks of operators would have kept the government's vital channels of communications open in the event of a nuclear attack. We also visited several newer, automated exchange rooms, which would have done the same job as the operators in the later years that the bunker was on standby.

Supernatural Subterranea

Exploration isn't the only reason to venture underground in the dark. A couple of years ago, I saw a subterranean event with a difference advertised, a ghost hunt in Drakelow Tunnels, an underground WWII factory. It seemed like a good opportunity to visit a location that rarely opened to the public and would soon be closed to visits for good.

Epilogue

The pursuit of hidden, forbidden, and off-limits places briefly put me in the spotlight. I've spoken about my fascination with underground exploration on various radio stations, including on a BBC Radio 4 programme called 'Subterranean Stories' presented by journalist, Dylan Winter. I returned to the village of Monkton Farleigh to be interviewed for the programme, which opened to the famous theme tune from 'The Wombles'.

If you're interested in learning more about the secrets that lie beneath Britain, be sure to check out 'Hidden, Forbidden & Off-Limits', which is available now from Amazon on paperback, hard cover, as an ebook for Kindle, or an audiobook on Audible.

Learn With Higgypop

Hosted by Paralearning in association with Higgypop, these courses on ghost hunting, paranormal investigations, and occult practices draw on the experience of our team of paranormal writers.

Diploma In Capturing & Analyzing Electronic Voice Phenomenon

This course gives you practical and useful knowledge of ghost hunting and paranormal research, which is invaluable when conducting your own paranormal investigations or as part of a group event.

View Course

Diploma In Parapsychology & Psychic Phenomena

This course gives you practical and useful knowledge of ghost hunting and paranormal research, which is invaluable when conducting your own paranormal investigations or as part of a group event.

View CourseMore Like This

Kate CherrellApril 14, 2025

Kate Cherrell's Debut Gothic Horror Novel 'Begotten' Arrives This May

BooksMarch 17, 2025

Revisiting 'Mind To Mind': René Warcollier's 1948 Book On Telepathy

Remote ViewingMarch 05, 2025

7 Things We Learnt About Remote Viewing From This Forgotten Book

BooksNovember 22, 2024

Richard Estep Explores The Demonic In His New Book 'In Search Of Demons'

See More on Audible

See More on Audible

Comments

Want To Join The Conversation?

Sign in or create an account to leave a comment.

Sign In

Create Account

Account Settings

Be the first to comment.