This page is more than one year old.

In the heart of Wiltshire lies Corsham, home to the mysterious Rudloe Manor site, a magnet that draws military historians, urban explorers, and conspiracy theorists from around the world. The entire area is steeped in mystery, with both operational and decommissioned military bases that have, at various times, been veiled under layers of secrecy, with a select few remaining so even today.

Join us as we delve deep into the subterranean world, navigating through an extensive network of over 60 miles of once-classified tunnels, including the legendary Burlington Bunker. But our exploration won't stop there. We'll be soaring high above, taking an aerial perspective using drone technology to unravel Corsham's covert military hideaways like never before.

Delving Into Corsham

Photo: Crown Copyright

The allure of the Rudloe area, however, is not so much about its surface as it is about what it conceals beneath. Beneath Corsham's rustic charm lies an astounding labyrinth, approximately 60 miles of tunnels expanding over a 270-acre site within a two-mile radius. A large segment of this subterranean marvel was carved from three ancient stone quarries dating back to around 1840.

These colossal quarries, namely Box Quarry, Tunnel Quarry, and Spring Quarry sit either side of the historic Box Tunnel, designed by none other than Isambard Kingdom Brunel, carrying the primary railway line to London.

In the mid-90s, Rudloe Manor piqued global interest when ufologists and bunker busters turned their attention towards the historic market town of Corsham, propelled by the whispers about the secrets lurking beneath. But how did this quaint Wiltshire town become such a hotspot for conspiracy theorists?

Even today, a drive along Westwells Road in Corsham hints at why conspiracy theorists were so captivated by the area two decades ago. Back then, information about the RAF base was scarce, and even less was known about the clandestine activities carried out underground.

The Ministry of Defence had kept mum about any underground activities in Corsham, but the curious minds were undeterred. They were tantalised by mysterious doorways burrowed into grassy mounds and air shafts punctuating the fields around the base - clear signs that something was indeed present beneath the earth.

The town of Corsham is built atop an extensive network of old stone quarries. The War Department began acquiring these quarries during the two World Wars, repurposing them as ammunition stores and underground factories.

Despite the end of the wars, the area's high-security presence persisted, sparking suspicions that the MOD was concealing something beneath Corsham. Investigators who probed the site often reported eerie encounters like being followed by unmarked cars or accosted by MOD security. Some even claimed surveillance by plain-clothed security personnel disguised as casual dog walkers.

It wasn't merely the 'no entry' signs or the bunker entrances that fed the conspiracy theorists' curiosity. The base was the subject of numerous rumours about its functions, and the MOD's flat denials only served to stimulate researchers' inquisitiveness further. What exactly were they trying to hide?

Rudloe Manor was rumoured to host several "ultra-secret" government projects and departments, including the Provost and Security Services, responsible for providing security vetting for various government departments, possibly even the MI5 and MI6.

Yet, the most tantalising rumour was that Rudloe Manor was the hub to which all UK UFO reports were forwarded. This led to the belief that the government agents in Corsham had more knowledge about extraterrestrials than they were letting on. Such rumours elevated Rudloe Manor's status to being referred to as the UK's Area 51, deemed the apex of security in the country.

The conspiracy theorists' persistence undoubtedly added to the stress of the Rudloe security personnel in the 90s. Still, their doggedness wasn't entirely in vain. In 2010, the MOD released documents under the Freedom of Information Act confirming the base's involvement in the UK's UFO reporting mechanism.

Until the early part of 1992, the Flying Complaints Flight, a part of the Provost and Security Services, acted as the central coordination point for UFO reports made to RAF stations around the country by the public. Though the department did address reports of flying saucers, their primary focus was on complaints regarding low flying aircraft.

These colossal quarries, namely Box Quarry, Tunnel Quarry, and Spring Quarry sit either side of the historic Box Tunnel, designed by none other than Isambard Kingdom Brunel, carrying the primary railway line to London.

In the mid-90s, Rudloe Manor piqued global interest when ufologists and bunker busters turned their attention towards the historic market town of Corsham, propelled by the whispers about the secrets lurking beneath. But how did this quaint Wiltshire town become such a hotspot for conspiracy theorists?

Even today, a drive along Westwells Road in Corsham hints at why conspiracy theorists were so captivated by the area two decades ago. Back then, information about the RAF base was scarce, and even less was known about the clandestine activities carried out underground.

The Ministry of Defence had kept mum about any underground activities in Corsham, but the curious minds were undeterred. They were tantalised by mysterious doorways burrowed into grassy mounds and air shafts punctuating the fields around the base - clear signs that something was indeed present beneath the earth.

The town of Corsham is built atop an extensive network of old stone quarries. The War Department began acquiring these quarries during the two World Wars, repurposing them as ammunition stores and underground factories.

Despite the end of the wars, the area's high-security presence persisted, sparking suspicions that the MOD was concealing something beneath Corsham. Investigators who probed the site often reported eerie encounters like being followed by unmarked cars or accosted by MOD security. Some even claimed surveillance by plain-clothed security personnel disguised as casual dog walkers.

It wasn't merely the 'no entry' signs or the bunker entrances that fed the conspiracy theorists' curiosity. The base was the subject of numerous rumours about its functions, and the MOD's flat denials only served to stimulate researchers' inquisitiveness further. What exactly were they trying to hide?

Rudloe Manor was rumoured to host several "ultra-secret" government projects and departments, including the Provost and Security Services, responsible for providing security vetting for various government departments, possibly even the MI5 and MI6.

Yet, the most tantalising rumour was that Rudloe Manor was the hub to which all UK UFO reports were forwarded. This led to the belief that the government agents in Corsham had more knowledge about extraterrestrials than they were letting on. Such rumours elevated Rudloe Manor's status to being referred to as the UK's Area 51, deemed the apex of security in the country.

The conspiracy theorists' persistence undoubtedly added to the stress of the Rudloe security personnel in the 90s. Still, their doggedness wasn't entirely in vain. In 2010, the MOD released documents under the Freedom of Information Act confirming the base's involvement in the UK's UFO reporting mechanism.

Until the early part of 1992, the Flying Complaints Flight, a part of the Provost and Security Services, acted as the central coordination point for UFO reports made to RAF stations around the country by the public. Though the department did address reports of flying saucers, their primary focus was on complaints regarding low flying aircraft.

Unravelling Spring Quarry

Photo: Crown Copyright

Nestled south of Box Tunnel lies Spring Quarry. In operation for a century under the Bath and Portland Stone Company, it churned out building stone until its closure. Yet, the quarry's history was to take an unexpected turn in 1941, during the Second World War, when the Ministry of Aircraft Production took over. The Quarry was soon transformed into the world's largest underground factory, stretching across a staggering 2.25 million square-foot site.

Christened the Beaverbrook underground aircraft factory, it became a secure sanctuary for workers from the Bristol Aerospace Company, the BSA Barrel Mill Company, and the Parnell Turret Company. Here, they carried on crafting essential aircraft parts, even under the pressing threats of wartime. Part of the quarry, in the northwest, was set aside for Dowty Engineering, but it never saw completion.

Post-war, the factory found new purpose as the Royal Navy repurposed its underground chambers for storage until the 1990s. In recognition of its historic interest and uniqueness, an area of Spring Quarry, dubbed the Quarry Operations Centre, has been designated a Grade II listed site. Among its unique features are murals by local artist Olga Lehmann. Crafted using leftover paints from the aircraft factory, these murals enlivened the vast underground canteen for the factory workers.

Since the late-90s, urban explorers, chasing the thrill of the unknown, have attempted to infiltrate Spring Quarry. But it hasn't been easy. The quarry entrances, largely situated on MOD property, are guarded tenaciously by base staff. However, determined explorers have managed to exploit a few weak spots over time.

There's an inconspicuous brick building on White Ennox Lane. Inside, a stairwell spirals 30 meters down into the quarry. Originally an emergency exit for the aircraft factory, the shaft also enabled access to utilities such as gas and electricity. After multiple break-ins, which involved cutting through metal grills and removing breeze blocks, the building's security has been substantially enhanced. It now appears impenetrable, possibly alarmed, with the surrounding bushes trimmed for improved visibility during the MOD police's regular patrols.

Another entry point was through Sands Quarry, which adjoins the southern end of Spring Quarry. A relatively smaller quarry spanning just 4.6 square miles, Sands Quarry was once the site of stone extraction by the Bath and Portland Stone company starting in 1890. Quarrying ceased in 1912, and the site saw little activity thereafter.

Sands Quarry wasn't converted by the War Department, but it was requisitioned. An emergency escape route was established through the old stone workings, with reflective metal checkpoints guiding the path from Spring Quarry to Sands Quarry's surface slope shaft, with the way lit only by torchlight.

Spring Quarry has now been fortified, largely because of its newest occupant: Ark, a secure data storage company based at Spring Park on Westwells Road. Although the specifics of Ark's underground usage remain obscure, the company revealed plans to utilise the space for server rooms. They aim to offer robust, secure data storage for government and enterprise-level clients, touting the potential to build Europe's largest "data reservoir."

Storing servers underground provides superior security and also reduces the need for cooling, making it one of the most sustainable and environmentally friendly services of its kind worldwide. Besides serving commercial contracts, Ark also manages data centre services for the MOD.

Despite the stringent security, television presenter Phillip Schofield successfully infiltrated the site in 2015. But what of the eastern end of Spring Quarry? That segment of the quarry conceals an even bigger secret.

Christened the Beaverbrook underground aircraft factory, it became a secure sanctuary for workers from the Bristol Aerospace Company, the BSA Barrel Mill Company, and the Parnell Turret Company. Here, they carried on crafting essential aircraft parts, even under the pressing threats of wartime. Part of the quarry, in the northwest, was set aside for Dowty Engineering, but it never saw completion.

Post-war, the factory found new purpose as the Royal Navy repurposed its underground chambers for storage until the 1990s. In recognition of its historic interest and uniqueness, an area of Spring Quarry, dubbed the Quarry Operations Centre, has been designated a Grade II listed site. Among its unique features are murals by local artist Olga Lehmann. Crafted using leftover paints from the aircraft factory, these murals enlivened the vast underground canteen for the factory workers.

Since the late-90s, urban explorers, chasing the thrill of the unknown, have attempted to infiltrate Spring Quarry. But it hasn't been easy. The quarry entrances, largely situated on MOD property, are guarded tenaciously by base staff. However, determined explorers have managed to exploit a few weak spots over time.

There's an inconspicuous brick building on White Ennox Lane. Inside, a stairwell spirals 30 meters down into the quarry. Originally an emergency exit for the aircraft factory, the shaft also enabled access to utilities such as gas and electricity. After multiple break-ins, which involved cutting through metal grills and removing breeze blocks, the building's security has been substantially enhanced. It now appears impenetrable, possibly alarmed, with the surrounding bushes trimmed for improved visibility during the MOD police's regular patrols.

Another entry point was through Sands Quarry, which adjoins the southern end of Spring Quarry. A relatively smaller quarry spanning just 4.6 square miles, Sands Quarry was once the site of stone extraction by the Bath and Portland Stone company starting in 1890. Quarrying ceased in 1912, and the site saw little activity thereafter.

Sands Quarry wasn't converted by the War Department, but it was requisitioned. An emergency escape route was established through the old stone workings, with reflective metal checkpoints guiding the path from Spring Quarry to Sands Quarry's surface slope shaft, with the way lit only by torchlight.

Spring Quarry has now been fortified, largely because of its newest occupant: Ark, a secure data storage company based at Spring Park on Westwells Road. Although the specifics of Ark's underground usage remain obscure, the company revealed plans to utilise the space for server rooms. They aim to offer robust, secure data storage for government and enterprise-level clients, touting the potential to build Europe's largest "data reservoir."

Storing servers underground provides superior security and also reduces the need for cooling, making it one of the most sustainable and environmentally friendly services of its kind worldwide. Besides serving commercial contracts, Ark also manages data centre services for the MOD.

Despite the stringent security, television presenter Phillip Schofield successfully infiltrated the site in 2015. But what of the eastern end of Spring Quarry? That segment of the quarry conceals an even bigger secret.

Burlington: The Hidden Citadel

Photo: Crown Copyright

Beyond Sites 1 and 2, there lies Site 3, better known as the Burlington Bunker. It captures the imagination as the UK's most intriguing bunker, a veritable urban explorer's dream.

Revered as the 'holy grail' of urban exploration, Burlington has its roots deep in the Cold War era. Still, it was only in 2004 that the Ministry of Defence (MOD) finally admitted the full extent of this underground facility when it was declassified. Designed as the Emergency Government War Headquarters, Burlington was equipped to safely shelter hundreds of Whitehall staff, government officials, and heads of public and security services for months following a nuclear strike on British soil.

Under the spectre of a potential Soviet nuclear attack, the British government set out to fortify a section of Spring Quarry. Completed in 1961, this site would become the wartime locus of power, accommodating the Prime Minister, cabinet office, national and local government agencies, intelligence and security advisors, and their support staff.

Ensconced within Burlington, the government would run the country as usual, aided by the Prime Minister's map room. The bunker's primary role was to serve as a communication hub, maintaining contact within the UK and with the outside world. To facilitate this, it housed a massive telephone exchange to keep the occupants connected with different parts of the country.

Burlington wore several different codenames throughout its history, such as the Hawthorn Central Government War Headquarters, the Emergency Government War Headquarters, Stockwell, Subterfuge, Turnstile, and most recently, Site 3, a nod to Rudloe sites 1 and 2.

The bunker was stocked with everything its inhabitants would need to survive for an extended period. It featured an infirmary equipped with examination rooms, wards, and a dental surgery. It had two spacious kitchens with a bakery, and a laundry facility, claimed to be the largest in Europe at the time.

A well-stocked library was a crucial part of the bunker. It contained a small but vital collection of books, maps, scientific and technical manuals, and acts of Parliament—knowledge that would be vital for rebuilding the devastated country.

The bunker even had dedicated accommodation for the Prime Minister. Despite its importance, the room reserved for the PM was quite similar to other staff accommodation in the complex, save for whitewashed walls and a private bathroom complete with a bath.

Access to the bunker was through various goods and passenger lifts and two escalators. The most well-known entry point, Passenger Lift 2, is a pair of unique wooden elevators, now out of service for decades. The top of the lift shaft and entrance can be spotted just inside the MOD's perimeter fence along Westwells Road.

Burlington remained stocked and on standby until the 1980s when the diminished threat from Russia led to its decommissioning. The bunker, having never been put to actual use, was finally acknowledged by the MOD in 2004.

Several myths about the Burlington bunker persist. Rumours include it having its own nuclear generator, an underground pub named the Red Lion, and even its own underground railway station. Although these are untrue, a subterranean station does exist in Corsham, but it's not in Burlington.

At the eastern end of Box Tunnel on the main train line from London, a private branch line darts underground at Corsham. However, this line serves Tunnel Quarry, located north of Burlington. In fact, one reason it took the MOD so long to declassify Burlington was its role for over a decade as a decoy site, diverting attention from the real secrets concealed in the neighboring Tunnel Quarry.

Revered as the 'holy grail' of urban exploration, Burlington has its roots deep in the Cold War era. Still, it was only in 2004 that the Ministry of Defence (MOD) finally admitted the full extent of this underground facility when it was declassified. Designed as the Emergency Government War Headquarters, Burlington was equipped to safely shelter hundreds of Whitehall staff, government officials, and heads of public and security services for months following a nuclear strike on British soil.

Under the spectre of a potential Soviet nuclear attack, the British government set out to fortify a section of Spring Quarry. Completed in 1961, this site would become the wartime locus of power, accommodating the Prime Minister, cabinet office, national and local government agencies, intelligence and security advisors, and their support staff.

Ensconced within Burlington, the government would run the country as usual, aided by the Prime Minister's map room. The bunker's primary role was to serve as a communication hub, maintaining contact within the UK and with the outside world. To facilitate this, it housed a massive telephone exchange to keep the occupants connected with different parts of the country.

Burlington wore several different codenames throughout its history, such as the Hawthorn Central Government War Headquarters, the Emergency Government War Headquarters, Stockwell, Subterfuge, Turnstile, and most recently, Site 3, a nod to Rudloe sites 1 and 2.

The bunker was stocked with everything its inhabitants would need to survive for an extended period. It featured an infirmary equipped with examination rooms, wards, and a dental surgery. It had two spacious kitchens with a bakery, and a laundry facility, claimed to be the largest in Europe at the time.

A well-stocked library was a crucial part of the bunker. It contained a small but vital collection of books, maps, scientific and technical manuals, and acts of Parliament—knowledge that would be vital for rebuilding the devastated country.

The bunker even had dedicated accommodation for the Prime Minister. Despite its importance, the room reserved for the PM was quite similar to other staff accommodation in the complex, save for whitewashed walls and a private bathroom complete with a bath.

Access to the bunker was through various goods and passenger lifts and two escalators. The most well-known entry point, Passenger Lift 2, is a pair of unique wooden elevators, now out of service for decades. The top of the lift shaft and entrance can be spotted just inside the MOD's perimeter fence along Westwells Road.

Burlington remained stocked and on standby until the 1980s when the diminished threat from Russia led to its decommissioning. The bunker, having never been put to actual use, was finally acknowledged by the MOD in 2004.

Several myths about the Burlington bunker persist. Rumours include it having its own nuclear generator, an underground pub named the Red Lion, and even its own underground railway station. Although these are untrue, a subterranean station does exist in Corsham, but it's not in Burlington.

At the eastern end of Box Tunnel on the main train line from London, a private branch line darts underground at Corsham. However, this line serves Tunnel Quarry, located north of Burlington. In fact, one reason it took the MOD so long to declassify Burlington was its role for over a decade as a decoy site, diverting attention from the real secrets concealed in the neighboring Tunnel Quarry.

Tunnel Quarry: The Underground Arsenal

Photo: Crown Copyright

Located to the north of Box Tunnel, Tunnel Quarry once served as a sub-depot of the Central Ammunition Depot. It was one of four sub-depots in the local area that collectively had the capacity to store an astounding 350,000 tons of ammunition—crucial to our efforts during World War II. The other three sub-depots were scattered across the broader region at Neston, Gastard, and Monkton Farleigh.

It was at Monkton Farleigh where my fascination with the area's underground mysteries was kindled in 2002. I had been conscious of the secret bunkers in the region for a while, but one Saturday afternoon, friends and I, armed with a copy of Nick McCamley's book 'Secret Underground Cities', ventured into Wiltshire. After exchanging a few emails with Nick, who guided me towards some of the underground facility entrances, we were on a mission to locate them.

Parking on a country lane, I barely grasped the colossal scale of what we were about to discover. We ambled along a small lane, previously an access road built by the War Department, leading to the bunker via three of its main entrances. The first entrance we stumbled upon was a dilapidated shed, previously the District 19 surface loading building.

The building, with its quaint charm, blended seamlessly into the English countryside. Had German planes soared overhead during the war, its seemingly innocuous facade would have remained undetected. Inside, the structure was deserted and neglected. Still, one corner housed a grand concrete archway leading down to the bunker. However, our descent via this "slope shaft" was blocked by a firmly bricked-up entrance.

As we strolled along the access road under the sun, we reached another barn-like structure, the District 20 loading building. Despite Nick's tip-off about this bunker access, I was still astonished to find the slope shaft unsealed and open.

Caught off guard by the open doorway, we weren't fully equipped for exploration, but curiosity prevailed. Carefully, we navigated 135 steps down into the abyss, 30 meters below. Our journey was dimly lit by a feeble pocket torch that could barely illuminate a few steps ahead, let alone the staircase bottom.

Reaching the staircase bottom was like stepping into a massive underground bunker that once served as an ammunition depot during the war, now lying in disrepair and marred by vandalism. As we stood engulfed in darkness, we were awed by the enormity of the bunker that sprawled out into pitch-black tunnels. Realizing that a single, faltering torch wouldn't suffice to explore the massive bunker, we reluctantly ascended back to the surface. The air became increasingly warmer and humid, a stark contrast to the cool underground air we left behind.

For the next few months, we exhaustively explored Monkton Farleigh Mine, this time adequately armed with better torches, overalls, and hard hats. Those were captivating summer days spent unraveling the dark labyrinth of tunnels beneath the village. I was utterly hooked from that moment on.

The Monkton Farleigh ammunition depot comprised of storage districts 12 to 20, all interconnected underground. Conversely, Tunnel Quarry in Corsham housed districts 1 through 11. Each district spanned approximately five acres, although District 1 was never converted due to a severe geological fault.

However, the rest of Tunnel Quarry underwent extensive renovations, including the construction of uniform storage bays, a flat and even floor, air conditioning, and lighting. New slope shafts were excavated into the quarry to facilitate ammunition movement, culminating on the surface at the Main Surface Loading Platform. This unique hexagon-shaped room provided access to all four shafts.

It was at Monkton Farleigh where my fascination with the area's underground mysteries was kindled in 2002. I had been conscious of the secret bunkers in the region for a while, but one Saturday afternoon, friends and I, armed with a copy of Nick McCamley's book 'Secret Underground Cities', ventured into Wiltshire. After exchanging a few emails with Nick, who guided me towards some of the underground facility entrances, we were on a mission to locate them.

Parking on a country lane, I barely grasped the colossal scale of what we were about to discover. We ambled along a small lane, previously an access road built by the War Department, leading to the bunker via three of its main entrances. The first entrance we stumbled upon was a dilapidated shed, previously the District 19 surface loading building.

The building, with its quaint charm, blended seamlessly into the English countryside. Had German planes soared overhead during the war, its seemingly innocuous facade would have remained undetected. Inside, the structure was deserted and neglected. Still, one corner housed a grand concrete archway leading down to the bunker. However, our descent via this "slope shaft" was blocked by a firmly bricked-up entrance.

As we strolled along the access road under the sun, we reached another barn-like structure, the District 20 loading building. Despite Nick's tip-off about this bunker access, I was still astonished to find the slope shaft unsealed and open.

Caught off guard by the open doorway, we weren't fully equipped for exploration, but curiosity prevailed. Carefully, we navigated 135 steps down into the abyss, 30 meters below. Our journey was dimly lit by a feeble pocket torch that could barely illuminate a few steps ahead, let alone the staircase bottom.

Reaching the staircase bottom was like stepping into a massive underground bunker that once served as an ammunition depot during the war, now lying in disrepair and marred by vandalism. As we stood engulfed in darkness, we were awed by the enormity of the bunker that sprawled out into pitch-black tunnels. Realizing that a single, faltering torch wouldn't suffice to explore the massive bunker, we reluctantly ascended back to the surface. The air became increasingly warmer and humid, a stark contrast to the cool underground air we left behind.

For the next few months, we exhaustively explored Monkton Farleigh Mine, this time adequately armed with better torches, overalls, and hard hats. Those were captivating summer days spent unraveling the dark labyrinth of tunnels beneath the village. I was utterly hooked from that moment on.

The Monkton Farleigh ammunition depot comprised of storage districts 12 to 20, all interconnected underground. Conversely, Tunnel Quarry in Corsham housed districts 1 through 11. Each district spanned approximately five acres, although District 1 was never converted due to a severe geological fault.

However, the rest of Tunnel Quarry underwent extensive renovations, including the construction of uniform storage bays, a flat and even floor, air conditioning, and lighting. New slope shafts were excavated into the quarry to facilitate ammunition movement, culminating on the surface at the Main Surface Loading Platform. This unique hexagon-shaped room provided access to all four shafts.

Corsham Computer Centre: The Underground Nerve Centre

Even today, the Corsham Computer Centre (CCC) stands as a covert government establishment, nestled within the eastern extremity of Tunnel Quarry, an area formerly known as Hudswell Quarry.

As an active facility, the CCC is shrouded in mystery. All that's known is that it was constructed during the 1980s within what was once District 9 of the ammunition depot, which is now isolated from the rest of the quarry. It can only be accessed via an elevator leading from a subtly concealed bunker-style entrance in Peel Circus.

Interestingly, the bunker was most likely constructed in a section of District 9 that had undergone additional modification during its original conversion. In contrast to the rest of the ammunition depot, a series of parallel concrete walls were erected here, with the intervening stone meticulously removed.

Having been cleared of stone, this section presented an open canvas for the builders to construct a self-contained, open-plan bunker. The project involved fortifying the old quarry ceiling with supports and reinforcing it with concrete to minimize the need for future maintenance.

During this construction phase, the Burlington decoy narrative came into play. Rumors circulated that the construction activity in the region was aimed at upgrading Burlington, effectively drawing attention away from the CCC.

At first glance, security at the site seems low-key. However, the entrance is encircled by dual perimeter fences and a dense barrier of vegetation and trees to keep the facility hidden from public view. The fence opens only for a single gate, which is continuously monitored by multiple CCTV cameras.

Beyond the gate lies an expansive mound of earth with a concrete-reinforced entrance burrowing into the side of the artificial hill. Upon entering, visitors find themselves in a stark reception area, with staff ensconced behind a protective glass panel. Two "test tube" security doors mark the pathway to the bunker's personnel elevator.

There are those who claim that the elevator descends to a minimalist, whitewashed corridor encircling an operations control room, revealing nothing more than a mundane water cooler. Tales circulate of an open-plan operations room beyond this corridor, resplendent with a wall of video displays and staff attending to terminals round-the-clock.

So, what indeed transpires within the confines of the CCC?

According to the MOD, the CCC functions as a data processing centre. This was confirmed by then-Secretary of State for Defence, Des Browne, in 2007 when he characterized the bunker as a "data processing facility in support of Royal Navy operations."

UK parliamentary documents revealed that the "work on software for Trident is carried out in the Corsham Computer Centre, also referred to as the Corsham Software Facility." These documents confirmed that this is an underground complex located near Basil Hill Barracks in Wiltshire.

Such information suggests that the CCC serves as part of the Submarine Command & Control programme, shouldering the responsibility of maintaining the software linked to the UK's nuclear deterrent, the Trident programme.

As an active facility, the CCC is shrouded in mystery. All that's known is that it was constructed during the 1980s within what was once District 9 of the ammunition depot, which is now isolated from the rest of the quarry. It can only be accessed via an elevator leading from a subtly concealed bunker-style entrance in Peel Circus.

Interestingly, the bunker was most likely constructed in a section of District 9 that had undergone additional modification during its original conversion. In contrast to the rest of the ammunition depot, a series of parallel concrete walls were erected here, with the intervening stone meticulously removed.

Having been cleared of stone, this section presented an open canvas for the builders to construct a self-contained, open-plan bunker. The project involved fortifying the old quarry ceiling with supports and reinforcing it with concrete to minimize the need for future maintenance.

During this construction phase, the Burlington decoy narrative came into play. Rumors circulated that the construction activity in the region was aimed at upgrading Burlington, effectively drawing attention away from the CCC.

At first glance, security at the site seems low-key. However, the entrance is encircled by dual perimeter fences and a dense barrier of vegetation and trees to keep the facility hidden from public view. The fence opens only for a single gate, which is continuously monitored by multiple CCTV cameras.

Beyond the gate lies an expansive mound of earth with a concrete-reinforced entrance burrowing into the side of the artificial hill. Upon entering, visitors find themselves in a stark reception area, with staff ensconced behind a protective glass panel. Two "test tube" security doors mark the pathway to the bunker's personnel elevator.

There are those who claim that the elevator descends to a minimalist, whitewashed corridor encircling an operations control room, revealing nothing more than a mundane water cooler. Tales circulate of an open-plan operations room beyond this corridor, resplendent with a wall of video displays and staff attending to terminals round-the-clock.

So, what indeed transpires within the confines of the CCC?

According to the MOD, the CCC functions as a data processing centre. This was confirmed by then-Secretary of State for Defence, Des Browne, in 2007 when he characterized the bunker as a "data processing facility in support of Royal Navy operations."

UK parliamentary documents revealed that the "work on software for Trident is carried out in the Corsham Computer Centre, also referred to as the Corsham Software Facility." These documents confirmed that this is an underground complex located near Basil Hill Barracks in Wiltshire.

Such information suggests that the CCC serves as part of the Submarine Command & Control programme, shouldering the responsibility of maintaining the software linked to the UK's nuclear deterrent, the Trident programme.

Primary Network Control Centre: The Communications Hub In The Quarry

Photo: Crown Copyright

Located at the opposing end of Tunnel Quarry is the area initially planned to serve as District 1 of the ammunition depot. Despite the presence of a significant geological fault, the Air Ministry, in 1943, undertook the herculean task of converting the area. The fault line that crisscrossed this section of the quarry made this project particularly challenging.

The intricate conversion work required galleries from the mining era to be precisely squared off and the floor graded. For easier access, an electric lift was installed from the surface, a feature that remains functional to this day.

The resultant conversion yielded approximately 30,000 square feet of office space and initially served as the hub for South West Control, a military communications centre. This centre housed a variety of communications switching equipment, telephone switchboards, and teleprinter equipment.

Later, the site earned the moniker of the Primary Network Control Centre (PNCC). It continued to facilitate military communication until its decommissioning in the 1990s.

Although it no longer bears the name PNCC, the facility continues to play a crucial role in military communications to this day. It most likely operates under the jurisdiction of the Global Operations Security Control Centre (GOSCC). After undergoing an upgrade in communications equipment post-2008, it seems to coincide with the multi-million-pound redevelopment of the new GOSCC building.

Near the GOSCC building, on the intersection of Westwells Road and Park Lane, one can spot a small green structure peeking through the fences. This structure marks the top of the 1943 lift shafts that descend directly into the PNCC. As most of the other lifts in Spring Quarry, Tunnel Quarry, and Burlington have been decommissioned, these lifts serve as one of the primary access routes into the subterranean complex today. The exceptions include Spring Park's lift, a former goods elevator, and the lift at the CCC.

The GOSCC surface building also hosts the Cyber Policy Unit, entrusted with the critical task of safeguarding the British Army's vital systems and computer networks, enabling servicemen to execute their missions globally. Comprising a surprisingly small, highly skilled team of technical staff, these are individuals who have an intimate understanding of MOD systems and their potential vulnerabilities. It is probable that this team maintains a presence within the PNCC.

The intricate conversion work required galleries from the mining era to be precisely squared off and the floor graded. For easier access, an electric lift was installed from the surface, a feature that remains functional to this day.

The resultant conversion yielded approximately 30,000 square feet of office space and initially served as the hub for South West Control, a military communications centre. This centre housed a variety of communications switching equipment, telephone switchboards, and teleprinter equipment.

Later, the site earned the moniker of the Primary Network Control Centre (PNCC). It continued to facilitate military communication until its decommissioning in the 1990s.

Although it no longer bears the name PNCC, the facility continues to play a crucial role in military communications to this day. It most likely operates under the jurisdiction of the Global Operations Security Control Centre (GOSCC). After undergoing an upgrade in communications equipment post-2008, it seems to coincide with the multi-million-pound redevelopment of the new GOSCC building.

Near the GOSCC building, on the intersection of Westwells Road and Park Lane, one can spot a small green structure peeking through the fences. This structure marks the top of the 1943 lift shafts that descend directly into the PNCC. As most of the other lifts in Spring Quarry, Tunnel Quarry, and Burlington have been decommissioned, these lifts serve as one of the primary access routes into the subterranean complex today. The exceptions include Spring Park's lift, a former goods elevator, and the lift at the CCC.

The GOSCC surface building also hosts the Cyber Policy Unit, entrusted with the critical task of safeguarding the British Army's vital systems and computer networks, enabling servicemen to execute their missions globally. Comprising a surprisingly small, highly skilled team of technical staff, these are individuals who have an intimate understanding of MOD systems and their potential vulnerabilities. It is probable that this team maintains a presence within the PNCC.

Browns Quarry: The Unseen Underbelly Of Military Operations

Photo: Crown Copyright

Venturing beyond Tunnel Quarry, we find ourselves drawn towards another fascinating subterranean site adjoined to its northern edge—Browns Quarry. Although smaller in size and unrelated to the ammunition depot, the Royal Engineers meticulously converted this quarry in tandem with the larger Tunnel Quarry.

Browns Quarry underwent some of the most comprehensive and demanding transformations among all MOD quarries. It harboured an underground operations room integral to the RAF's Command Centre for No. 10 Group. The extensive renovations necessitated the construction of two formidable chambers, each measuring 15 square meters and boasting a height of 13 meters, replete with two mezzanine observation floors.

Adorned in a unique palette of greens and yellows, the operations room walls were meticulously designed to minimise distractions for the operators. At the heart of the control room, a plotting table allowed controllers, stationed on the two wooden mezzanine floors above, to monitor enemy advances towards Britain.

This control room supervised nine fighter airfields in the West of England and Wales, which together housed 19 squadrons deploying 113 aircraft. The group commander, ensconced in the gallery, would scramble appropriate squadrons to intercept the enemy, guided by information relayed from the fighter command headquarters at Bentley Priory in Stanmore, Middlesex.

By 1945, the room had transformed into a radar training centre, and by 1951, it served as the Section Operations Centre for the United Kingdom Radar Air Defence System, codenamed ROTOR. However, by late 1955, control functions had relocated, and the room was stripped bare of its fixtures.

In its later life, the quarry became part of the CDCN, the Command Defence Communications Network. Nestled beneath Skynet Drive, the bunker forms the foundation of a modern building that serves as the nexus of a fortified satellite communications network. This network primarily serves the UK armed forces, and also various other governments and organisations worldwide.

The military communications network, aptly named Skynet, is currently in its fifth generation and is operated out of Corsham by Airbus Defence & Space. The first of four Skynet 5 satellites, launched by an Ariane 5 rocket in 2007, has been tailored to support smaller, low powered, tactical terminals.

These satellites are nuclear hardened, equipped with anti-jamming countermeasures, and laser protection. They feature fully steerable downlink spot beams that direct secure and encrypted data uplinks to British armed forces personnel deployed in far-flung locations like Afghanistan, the Falklands, Cyprus, and onboard naval vessels. The network is managed from the CDCN building in Corsham, via a satellite uplink located at nearby RAF Colerne.

Access to Browns Quarry remains restricted. However, from what little has been observed, it seems the underground site remains in good condition. Given its strategic location directly beneath their control room and accessibility via a lift shaft in the car park—a feature mirroring the one serving PNCC—it's plausible that the programme still utilises this subterranean space.

Browns Quarry underwent some of the most comprehensive and demanding transformations among all MOD quarries. It harboured an underground operations room integral to the RAF's Command Centre for No. 10 Group. The extensive renovations necessitated the construction of two formidable chambers, each measuring 15 square meters and boasting a height of 13 meters, replete with two mezzanine observation floors.

Adorned in a unique palette of greens and yellows, the operations room walls were meticulously designed to minimise distractions for the operators. At the heart of the control room, a plotting table allowed controllers, stationed on the two wooden mezzanine floors above, to monitor enemy advances towards Britain.

This control room supervised nine fighter airfields in the West of England and Wales, which together housed 19 squadrons deploying 113 aircraft. The group commander, ensconced in the gallery, would scramble appropriate squadrons to intercept the enemy, guided by information relayed from the fighter command headquarters at Bentley Priory in Stanmore, Middlesex.

By 1945, the room had transformed into a radar training centre, and by 1951, it served as the Section Operations Centre for the United Kingdom Radar Air Defence System, codenamed ROTOR. However, by late 1955, control functions had relocated, and the room was stripped bare of its fixtures.

In its later life, the quarry became part of the CDCN, the Command Defence Communications Network. Nestled beneath Skynet Drive, the bunker forms the foundation of a modern building that serves as the nexus of a fortified satellite communications network. This network primarily serves the UK armed forces, and also various other governments and organisations worldwide.

The military communications network, aptly named Skynet, is currently in its fifth generation and is operated out of Corsham by Airbus Defence & Space. The first of four Skynet 5 satellites, launched by an Ariane 5 rocket in 2007, has been tailored to support smaller, low powered, tactical terminals.

These satellites are nuclear hardened, equipped with anti-jamming countermeasures, and laser protection. They feature fully steerable downlink spot beams that direct secure and encrypted data uplinks to British armed forces personnel deployed in far-flung locations like Afghanistan, the Falklands, Cyprus, and onboard naval vessels. The network is managed from the CDCN building in Corsham, via a satellite uplink located at nearby RAF Colerne.

Access to Browns Quarry remains restricted. However, from what little has been observed, it seems the underground site remains in good condition. Given its strategic location directly beneath their control room and accessibility via a lift shaft in the car park—a feature mirroring the one serving PNCC—it's plausible that the programme still utilises this subterranean space.

Unravelling the Mystery: A Deep Dive Into Burlington

Photo: Crown Copyright

You might be wondering how one can uncover the veiled mysteries lurking beneath Corsham. The answer lies in the personal experiences of intrepid explorers such as Steve Higgins, who has recent written a book about the subterranean secrets in the area. Steve was given the unique opportunity to probe the depths of Site 3. Even in the absence of UFO sightings and ultra-secret projects, this underground marvel exudes an air of fascination.

Steve has not only navigated the disused bunkers scattered throughout the Corsham area, but he was also privileged to partake in an exclusive tour of Burlington itself back in 2008. On a chilly Saturday morning in February, Steve and seven companions congregated at what is now known as JSU (Joint Service Unit) Corsham.

True to its reputation, security was stringent. Each visitor was required to exit their vehicle and sign in at the guardhouse located at the gate. After confirming their identity and obtaining visitor passes, the party then proceeded through the premises. The drive took them past command and communication buildings shrouded in secrecy, offering an exhilarating glimpse into the covert operations of the facility.

Following this brief excursion, the party exchanged their initial passes for another set at a smaller guard hut. These new passes granted them access to the underground realm that awaited. The excitement grew palpable as they entered a small green building. All it contained were two elevator doors and a single, tantalising button: 'down.'

Emerging from the elevator about 30 meters underground, the group was greeted by a well-lit subterranean corridor. It could have easily been mistaken for an ordinary hallway in a hospital or office block, complete with pristine white walls, fluorescent strip lights, and a light green tiled floor. Its only giveaway was the conspicuous absence of windows.

This pristine corridor was part of the Primary Network Control Centre (PNCC), an active component of the MOD site at Corsham. The guide informed the group that this part of the quarry was strictly off-limits to cameras. After a brief health and safety briefing, and yet another sign-in, they were ushered into Burlington.

Stepping through large dust protection doors, they noticed an immediate change in the surroundings. They left behind the modern tunnels of PNCC, stepping into the remnants of the 1950s era Burlington Site 3 tunnels.

The labyrinthine bunker was marked by wide underground roadways, each bearing an American-style street name such as "First Avenue." These roads led to 22 distinct areas within the bunker, each serving a different function—from store rooms and accommodation to government offices, BBC studios, and a massive map room for the Prime Minister and war cabinet.

The group marvelled at the generator hall, kitchens, laundry, and air treatment utilities, all indispensable for the bunker's inhabitants' survival. The tour spanned four and a half hours, a journey through a maze of tunnels that have been carefully preserved for decades.

In the heart of the bunker, a vast underground canteen offered a glimpse into the Cold War era. The table was meticulously set with plates, cutlery, and even a faux fruit bowl, creating a vivid tableau of what life might have looked like had the bunker been called into action.

The group also visited the massive wooden telephone exchange room, where operators would have maintained the country's communications in the event of a nuclear attack. The tour also included a stop at several newer, automated exchange rooms, which would have assumed the same responsibilities in later years.

As part of the tour, the MOD staff arranged medical supplies in a small hospital ward, demonstrating how it was originally designed. The group was chauffeured between points of interest on two seven-seater electric buggies, adding a thrilling dimension to the exploration.

As their time underground dwindled, the party ventured into another adjoining MOD subterranean space—Tunnel Quarry. They were shown the colossal underground railway station, which played a critical role during World War II, facilitating the transportation of ammunition.

Their visit to Tunnel Quarry was brief, and they were explicitly kept away from storage districts 8 and 9, where CCC was nestled within the existing underground space. The immensity of what lies beneath Corsham is difficult to articulate. Burlington alone encompasses roughly 20% of the total underground space, stretching over an area approximately 1km by 200m.

Perhaps there are more secrets awaiting discovery in Corsham, but it's a privilege to have caught a glimpse of its hidden underground world. As for the mysteries that remain cloaked in the enveloping darkness, they are probably best left unknown.

Steve has not only navigated the disused bunkers scattered throughout the Corsham area, but he was also privileged to partake in an exclusive tour of Burlington itself back in 2008. On a chilly Saturday morning in February, Steve and seven companions congregated at what is now known as JSU (Joint Service Unit) Corsham.

True to its reputation, security was stringent. Each visitor was required to exit their vehicle and sign in at the guardhouse located at the gate. After confirming their identity and obtaining visitor passes, the party then proceeded through the premises. The drive took them past command and communication buildings shrouded in secrecy, offering an exhilarating glimpse into the covert operations of the facility.

Following this brief excursion, the party exchanged their initial passes for another set at a smaller guard hut. These new passes granted them access to the underground realm that awaited. The excitement grew palpable as they entered a small green building. All it contained were two elevator doors and a single, tantalising button: 'down.'

Emerging from the elevator about 30 meters underground, the group was greeted by a well-lit subterranean corridor. It could have easily been mistaken for an ordinary hallway in a hospital or office block, complete with pristine white walls, fluorescent strip lights, and a light green tiled floor. Its only giveaway was the conspicuous absence of windows.

This pristine corridor was part of the Primary Network Control Centre (PNCC), an active component of the MOD site at Corsham. The guide informed the group that this part of the quarry was strictly off-limits to cameras. After a brief health and safety briefing, and yet another sign-in, they were ushered into Burlington.

Stepping through large dust protection doors, they noticed an immediate change in the surroundings. They left behind the modern tunnels of PNCC, stepping into the remnants of the 1950s era Burlington Site 3 tunnels.

The labyrinthine bunker was marked by wide underground roadways, each bearing an American-style street name such as "First Avenue." These roads led to 22 distinct areas within the bunker, each serving a different function—from store rooms and accommodation to government offices, BBC studios, and a massive map room for the Prime Minister and war cabinet.

The group marvelled at the generator hall, kitchens, laundry, and air treatment utilities, all indispensable for the bunker's inhabitants' survival. The tour spanned four and a half hours, a journey through a maze of tunnels that have been carefully preserved for decades.

In the heart of the bunker, a vast underground canteen offered a glimpse into the Cold War era. The table was meticulously set with plates, cutlery, and even a faux fruit bowl, creating a vivid tableau of what life might have looked like had the bunker been called into action.

The group also visited the massive wooden telephone exchange room, where operators would have maintained the country's communications in the event of a nuclear attack. The tour also included a stop at several newer, automated exchange rooms, which would have assumed the same responsibilities in later years.

As part of the tour, the MOD staff arranged medical supplies in a small hospital ward, demonstrating how it was originally designed. The group was chauffeured between points of interest on two seven-seater electric buggies, adding a thrilling dimension to the exploration.

As their time underground dwindled, the party ventured into another adjoining MOD subterranean space—Tunnel Quarry. They were shown the colossal underground railway station, which played a critical role during World War II, facilitating the transportation of ammunition.

Their visit to Tunnel Quarry was brief, and they were explicitly kept away from storage districts 8 and 9, where CCC was nestled within the existing underground space. The immensity of what lies beneath Corsham is difficult to articulate. Burlington alone encompasses roughly 20% of the total underground space, stretching over an area approximately 1km by 200m.

Perhaps there are more secrets awaiting discovery in Corsham, but it's a privilege to have caught a glimpse of its hidden underground world. As for the mysteries that remain cloaked in the enveloping darkness, they are probably best left unknown.

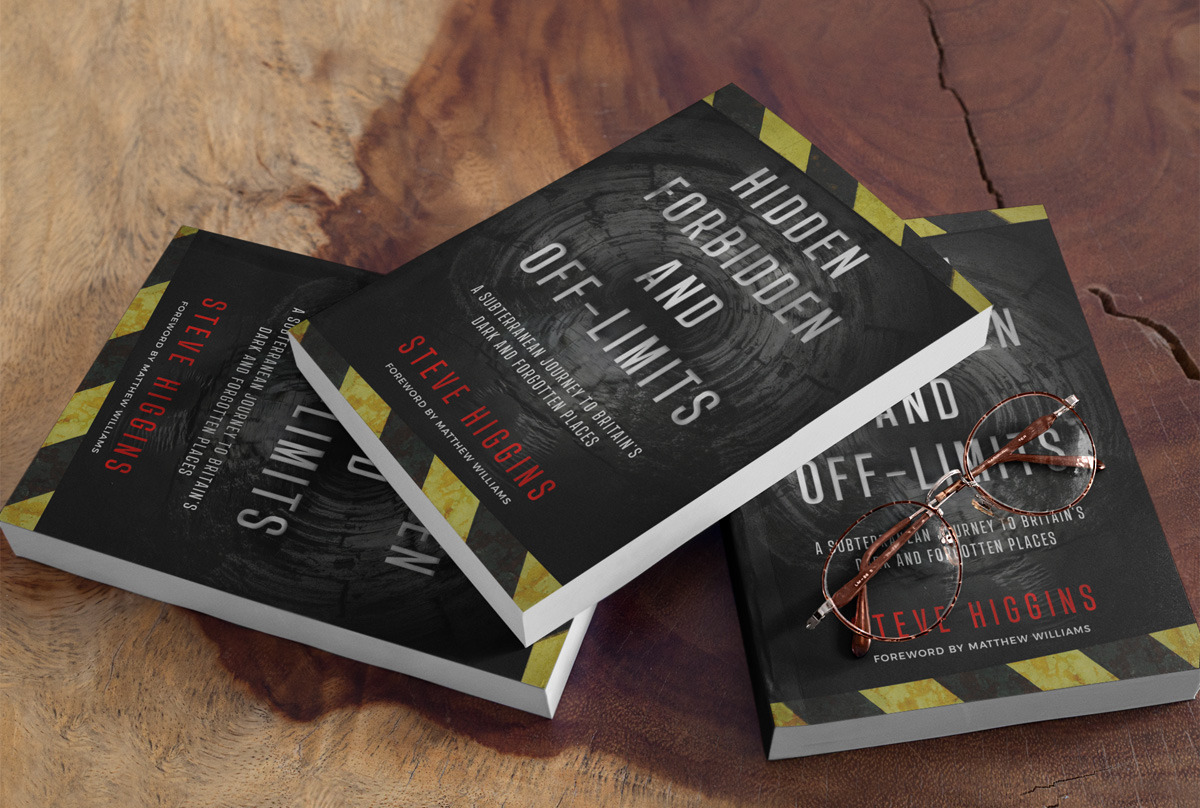

A Subterranean Journey To Britain's Dark & Forgotten Places

All of these formerly top secret locations are featured in much more detail in Steve Higgins' new urban and underground exploration book 'Hidden, Forbidden & Off-Limits'.

Having spent much of his professional life honing his creative skills working at some of the country's biggest brands in London, Steve has now returned to the South West of England - the region where he embarked on his first underground trip as a teen, an area so rich with subterranean secrets that Steve couldn't resist the thrill of urban exploration.

Circumvent the anti-trespass barriers, dodge the bats, and descend into these hidden landscapes to discover why people are so fascinated by the unknown worlds beneath their feet. With a foreword by Matthew Williams, the urban explorer and ufologist who helped shine a light on many of the government's underground coverups.

If you're interested in learning more about the secrets that lie beneath Britain, be sure to check out 'Hidden, Forbidden & Off-Limits', which is available now from Amazon on paperback, hard cover, as an ebook for Kindle, and as an audiobook on Audible.

© Crown Copyright Notice: Images on this page are reproduced with the permission of the Controller of His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Further Reading

Dive into the world of the paranormal and unexplained with books by Higgypop creator and writer Steve Higgins.

Demystifying The Oracle

A balanced look at Ouija boards, exploring whether they are toys, tools, or dangerous occult devices.

Buy Now

The Killamarsh Poltergeist

The story of a family in Killamarsh experiencing strange and unexplained events in their home.

Buy NowMore Like This

Kate CherrellApril 14, 2025

Kate Cherrell's Debut Gothic Horror Novel 'Begotten' Arrives This May

BooksMarch 17, 2025

Revisiting 'Mind To Mind': René Warcollier's 1948 Book On Telepathy

Remote ViewingMarch 05, 2025

7 Things We Learnt About Remote Viewing From This Forgotten Book

BooksNovember 22, 2024

Richard Estep Explores The Demonic In His New Book 'In Search Of Demons'

See More on Audible

See More on Audible

Comments

Want To Join The Conversation?

Sign in or create an account to leave a comment.

Sign In

Create Account

Account Settings

Be the first to comment.