Monkton Farleigh Mine

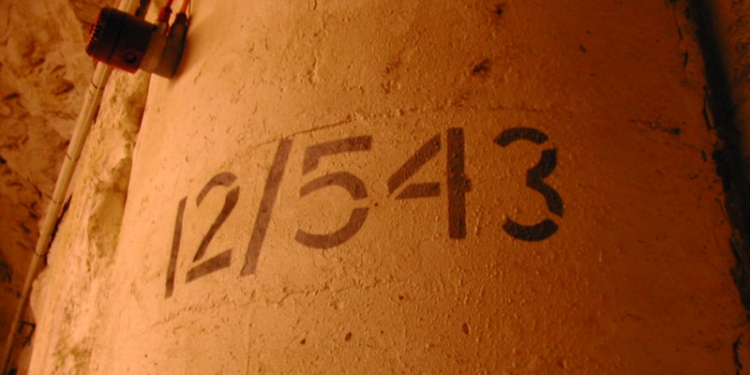

This former Bath stone quarry was converted in to a sub-depot of the Central Ammunitions Depot. The site consists of two areas, the main storage area - districts 12 to 18 and connect via a drift, districts 19 and 20. Each storage district was divided up in to numbered storage bays, passage ways were fitted with conveyor to transport crates of ammunition around the mine.

Monkton Farleigh, Wiltshire

Grid Reference: ST798660

No Access

This site is in private hands and parts of the quarry are occupied by a secure storage company, the rest of the quarry is sealed for security.

Monkton Farleigh Mine History

In 1881 the hills on the North Western side of Monkton Farleigh village were quarried for Bath Stone. By the time the quarries closed in 1930 the whole of the hill was riddled with roughly 300 acres of tunnels.

During the build up to WW2 the War Department decided that there was a need for a large underground ammunitions store. It was decided that the required space could be obtained by converting four quarries, these four formed what was collectively known as the Central Ammunitions Depot Corsham. Monkton Farleigh mine was acquired and became the biggest of the four sub components, a total of two and a half million square foot was converted.

The three other sub-depots were Tunnel Quarry at Corsham, Eastlays Quarry at Gastard and nearby Ridge Quarry.

Extensive conversion work was carried out at Monkton Farleigh, existing slope shafts were adapted and four new slope shafts were sunk. Above each of these slope shafts and loading shed building was built. Two service hatches and many air shafts were driven down in to the workings.

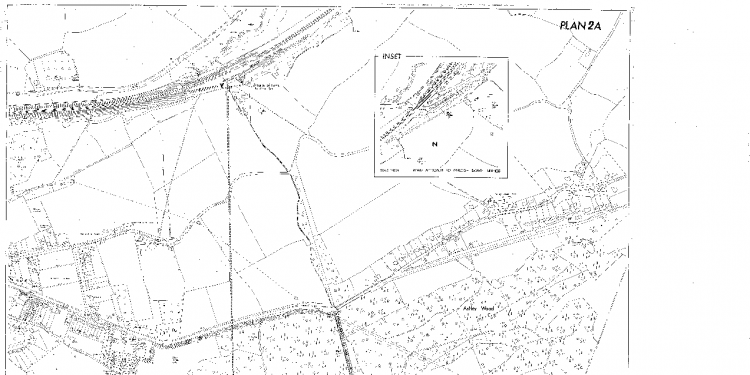

The site was served by an aerial rope way which transported the ammo cases from the main GWR line at Ashley. The rope ways needed to be replaced due to its vulnerability to attacks from air. A straight tunnel was bored stretching over a mile underground between Monkton and Farleigh Down Sidings.

The depot was gradually completed and filled with ammunition district by district until its completion in 1941, it was able to hold up to 120,000 tons of ammunition.

Huge amounts of funds were pumped in to the site after the war to maintain its condition until 1960 when it was decided to be surplus. The site was run down over the next few years while the last of the ammunition was depleted.

Monkton Farleigh Bunker Busted. The term "busted" got the makers of this video a lot of flak. People tend to use the term "urbex" these days. However, the explorers didn't actually break and enter or "bust" their way in, they simply walked in through open door, gates, holes in the ground.

The Complete History Of Monkton Farleigh

Welcome to the village of Monkton Farleigh on the Wiltshire border between Bath and Corsham...

This small village has been home to a big secret for the last sixty years or so. From the main road through Monkton Farleigh there are very few clues to what has gone on in the past here until you take a closer look.

On entering the village from the North the first thing you come across is a large concrete block this marks the location where a military road block would have stood during world war 2. Further along the road you come across a high fenced and highly secured yet rather small building followed by the brick chimney of an old boiler house.

So what is this rural villages big secret?

The hills on the North Western side of Monkton Farleigh village have been worked for Bath stone for over 200 years from open quarries. In 1881 the quarrying was taken underground with mines to follow the layer of highly sought after grand olite limestone which was formed in the Jurassic period. The stone was used for the construction of most of Bath’s famous buildings as well as Buckingham Palace and many stately homes across the country.

The many different quarries which were driven in to the rock in the Monkton area, eventually started to run in to each other underground by the time the mines closed down in 1930 the whole of Farleigh Down was riddled with roughly 300 acres of interconnecting underground workings and tunnels.

The abandoned mines were taken over by a village farmer by the name of Sir Charles Hobhouse, at this time he owned most of the land in Monkton Farleigh as well as all of the mine workings under the village.

With the threat of war looming the war department decided that there was a need for a large underground ammunitions store. Many quarries were surveyed around the Corsham area. It was decided that the required space could be obtained by converting four quarries, these four formed what was collectively known as the Central Ammunitions Depot Corsham. Monkton Farleigh mine was acquired from the Hobhouse estate by the MOD, this became the biggest of the four sub components, a total of two and a half million square foot was converted.

The other depots, all located around Corsham were, Tunnel Quarry in Wiltshire, this site is still owned by the ministry of defence, the abandoned Ridge Quarry in Neston and in Gastard, Eastlays Quarry which is now used by Octavian Wines as a storage and distribution depot.

The work at Monkton Farleigh started by adapting an existing slope shaft, now known as main East slope shaft and four new slope shafts were driven down to the workings. Above each of these slope shafts and loading shed building was built. The only shaft which did not have it’s own building was the remote South East slope shaft which was built as an emergency exit. Each of the building had wooden poles which stood high over the building tops, these suspended a camouflage sheet, disguising the loading bays from the air.

Thousands of tons of loose stone was brought to the surface and piled up in a field 100 feet above the main part of the storage area to a depth of about eight feet. This added extra strength to the main districts of the mine.

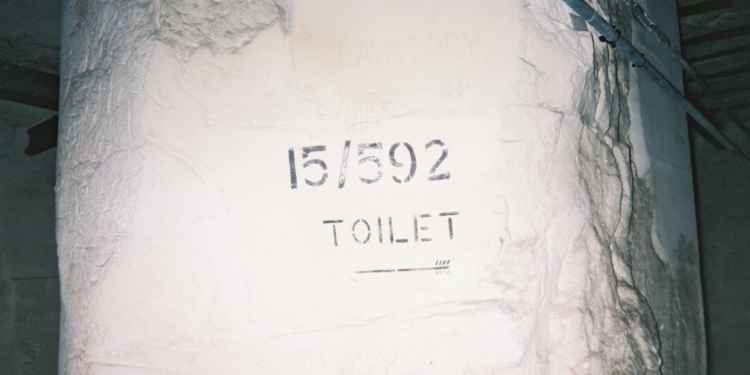

Two service hatches and many air shafts were driven down in to the workings, these feed an elaborate network of air conditioning and ventilation which was essential to maintain the correct storage conditions for the vital stores. Roughly 200 hundred toilets were installed for the workers.

The walls in Monkton Farleigh were corseted and re-enforced with concrete, the floor was flattened and covered in Colas, a spark-proof asphalt which contained coal dust. In some places there was such a rush to get the ammo in to the depot that when the stocks were piled in the floor was still wet resulting in the imprints of ammo cases in the floor which are still visible today.

Ridge Quarry, a sister depot making up part of the Central Ammunitions Depot, work was started to convert the mine but due to the costs being higher than expected the project was abandoned in it’s midst’s. Walking around the quarry now shows how some of the pillars had been corseted but were never completed. These would have eventually been white washed to produce the same finish as that of Monkton Farleigh and the rest of the Central Ammunitions Depot.

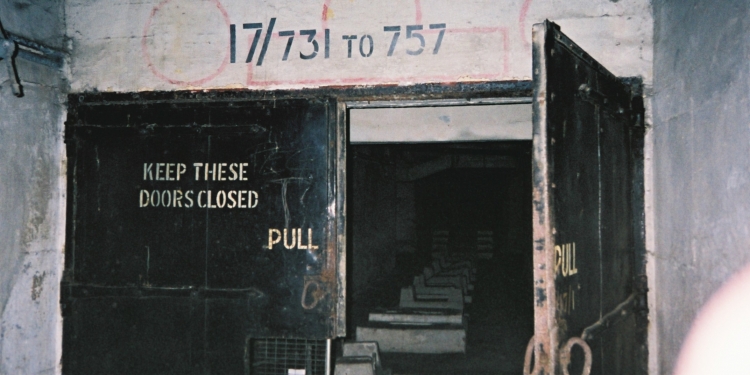

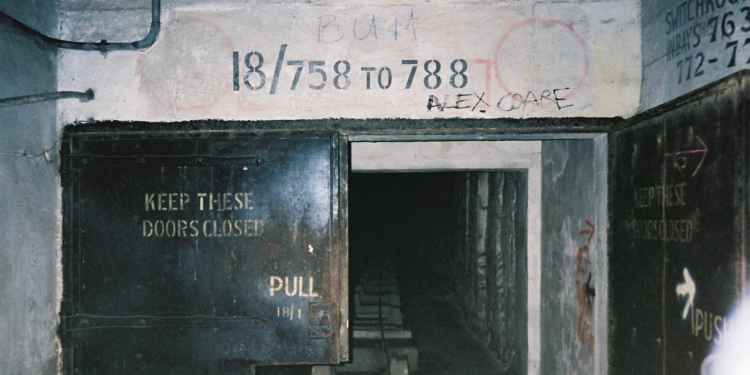

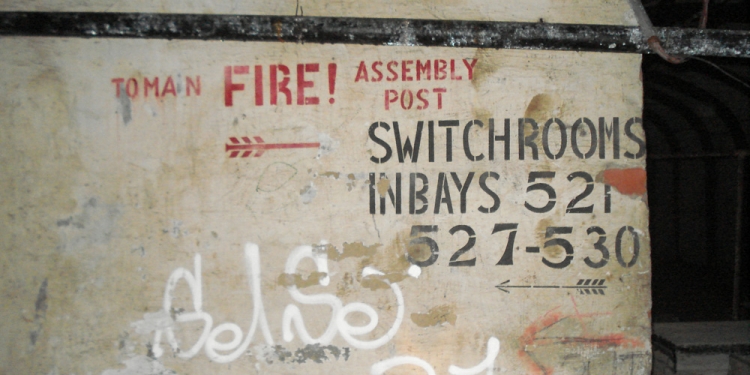

The main area of the Monkton Farleigh mine was divided in to six storage districts, 12 to 18, district 13 was never built as it was considered unlucky. There were two main haulage ways known as Main East and Main West. The northern end of both of these tunnels surfaced in to loading sheds, the Southern end of the tunnels terminated at the bottom of the mine in District 18. At the end of Main East corridor was the opening in to the South East emergency exit.

A massive under pinning operation was carried out in District 12, all the existing pillars were removed and the whole district was rebuilt with regular, rectangular storage bays.

The site was served by an arial rope way which transported the ammo cases from the main GWR line at Ashley. The rope ways needed to be replaced due to it’s vulnerability to attacks from air. A straight tunnel was bored stretching over a mile underground between Monkton and Farleigh Down Sidings. A conveyor belt was used to move the ammunition from the depot to the train line. The lower end of the tunnel opened up in to an underground marshaling yard and a large platform for loading and unloading the ammo.

Once the conversion was complete Monkton Farleigh Mine consisted of three main areas. The main storage area, districts 12 through to 18. Districts 19 and 20 were converted as temporary storage areas and Farleigh Down Tunnel the mile long connection to Ashley. The Western side of district 19 was walled off from the rest of the old mine workings. Part of these old working were originally going to be included in to district 19, the area was known as ‘K District’ the original war department markings can still be seen around the mine today.

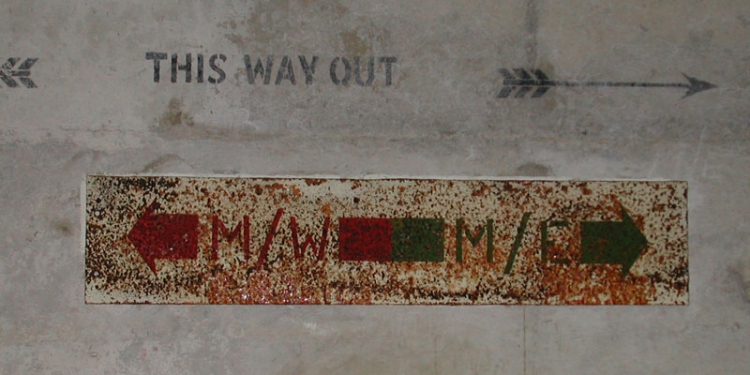

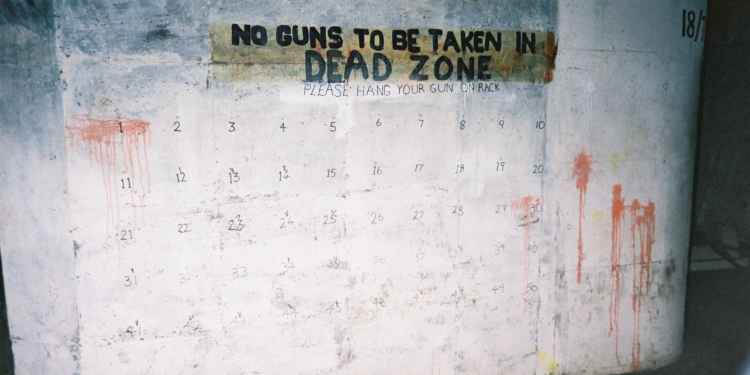

Each storage district was divided up in to numbered storage bays, main haulage ways were fitted with conveyor belts to transport crates of ammunition around the mine. They were taken off of the conveyor belt and taken to a storage bay using a sack truck where it would then be stacked.

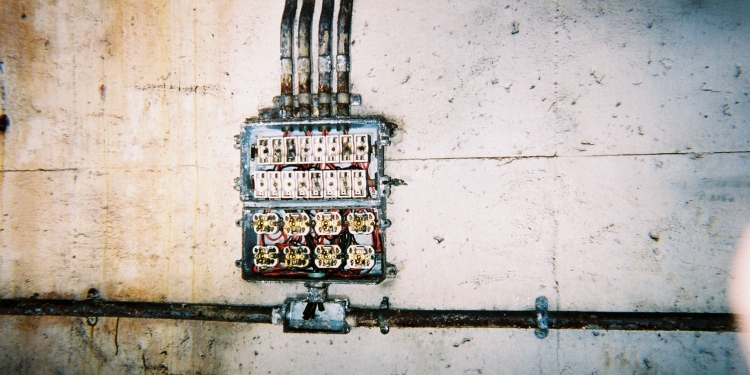

The storage districts were well constructed, well lit by thousands of light bulbs and air conditioned. The complex had it’s own underground power station and air conditioning plant. Above ground two buildings served as a boiler house and a cooling plant for the air conditioning systems. These two buildings are now used as a commercial business premises by Bannerdown Benching, the original chimney still exists but is not in use.

The depot was gradually completed and filled with ammunition district by district until it’s completion in 1941, it was now able to hold up to 120,000 tons of ammunition. The depot was fully stocked within a year.

Huge amounts of funds were pumped in to the site after the war to maintain it’s condition until 1960 when it was decided to be surplus. The site was run down over the next few years while the last of the ammunition was depleted.

Monkton Farleigh mine was sold off by the Ministry of Defence in 1975, during it’s period of disuse it fell victim to a spate of vandalism. Conveyors were ripped out, electrical fittings were stolen, air conditioning trunking was ripped out for the iron by scarp merchants and the walls sprayed with graffiti.

In 1984, came a new era for the mine when it was acquired by local man, Nick McCamley. Nick planned to restore the mine, which was by this time in very poor condition, and open it to the public as a tourist attraction. Nick got the full support of Ministry of Defence staff in Corsham and was given access to the fixtures and fitting in the still MOD owned, sister depot, Tunnel Quarry to help with the restoration project.

The museum was a success, visitors flocked from all over the world to visit what was, at the time, a very unusual tourist attraction. Sadly in 1990 the freehold of the museum was purchased by a Cambridge based company headed by George Backhurst.

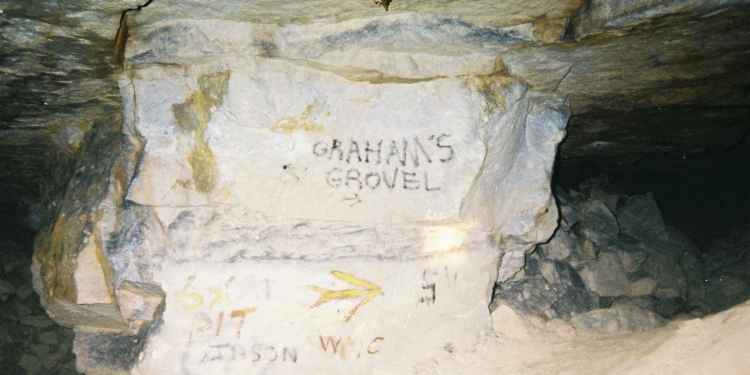

In 1989 during Nick’s occupation of the mine he and a gang of helpers opened an old tunnel running from District 20 in to the workings in Browns Folly Mine which was sealed off by the war department almost sixty years ago. It took the team almost two years to move the loose stone which back filled the last 200 feet of the drift, this route is now known by cavers as “Graham’s Grovel”. Before the 19/20 Drift was bored in 1943 the old drift was the only route in to District 20. The 19/20 Drift connected the main haulage ways in District 20 to the main haulage ways of District 19 and then on to main west corridor.

The mine fell in to disuse once more, all the hard work put in to restore the museum was lost when vandals and thieves once again moved in. One local scrap dealer ripped out parts of the air conditioning trunking and lay them on a hard standing on the surface, he tried to flatten the iron ducts with a steam roller he had acquired for the job to make the iron easy to sell on. However his plan failed, the steam roller just pushed the air conditioning trunks along the roadway and didn’t manage to crush them.

Advertisement ‐ Content Continues Below.

The Present

In 1996 the main part of the mine was acquired by Wansdyke Security, a secure warehousing business, specialising in the secure storage of documentation. The company had been operating from near by Brocklease Quarry since 1954 and another ex-war department quarry, Westwood since the mid-eighties. The company offers secure storage solutions to government departments, local and health authorities, defence and blue chip companies from the financial and commercial sector, as well as a wide range of industries and professions.

Wansdyke Security have secured their areas of the quarry and sealed them off from districts 19 and 20. The fate of districts 19 and 20 is uncertain, they now lay empty and decaying still in the hands of George Backhurst. This area of the quarry is closely watched by Stephen Weeks, a business man with grand designs for the former ammunition store. His wild plans involve building a replica of Bath’s Roman spa underground. As Bath is so congested he believes that tourists will flood in to see his replica with the offer of ample parking.

As for Farleigh Down Tunnel, the mile long tunnel leading to the depot, this now lays empty and disused, plans for this area included a mushroom farm, a recycling centre and paddocks but all of these plans have failed due to planning restrictions leaving the tunnel to slowly deteriorate.

The secure storage facility at Monkton Farleigh is still surrounded by a certain air of mystery and speculation. Wansdyke are understandably very paranoid about access to their storage area. I contacted them during the research for this project and they were very unwilling to help in anyway. In recent months Wansdyke Security have also been contacted by the BBC, an author as well as may individuals and groups who are interested in a tour of this piece of history. This cagey attitude towards public has caused some to come to the conclusion that there is more to the site than meets the eyes. As to what really goes on there we will never know, do they really just store people’s bank details and house deeds or are there links between Wansdyke Security and the government?

During the site’s time as a museum a Russian diplomat demanded a tour of the attraction, he demanded that it was closed to the public for the day and he was given an exclusive extensive tour of it alone. The diplomat asked to see every area of the ammunition store and refused to believe that he had seen the whole sight. He was convinced that the museum was a cover for something more sinister. He left at the end of the day still convinced that down a dark tunnel somewhere was a government office or a secret storage area.

UndergroundApril 06, 2017

15 Years On: My First Underground Trip

Monkton Farleigh Is Part Of CAD Corsham

UndergroundApril 15, 2013

Central Ammunitions Depot

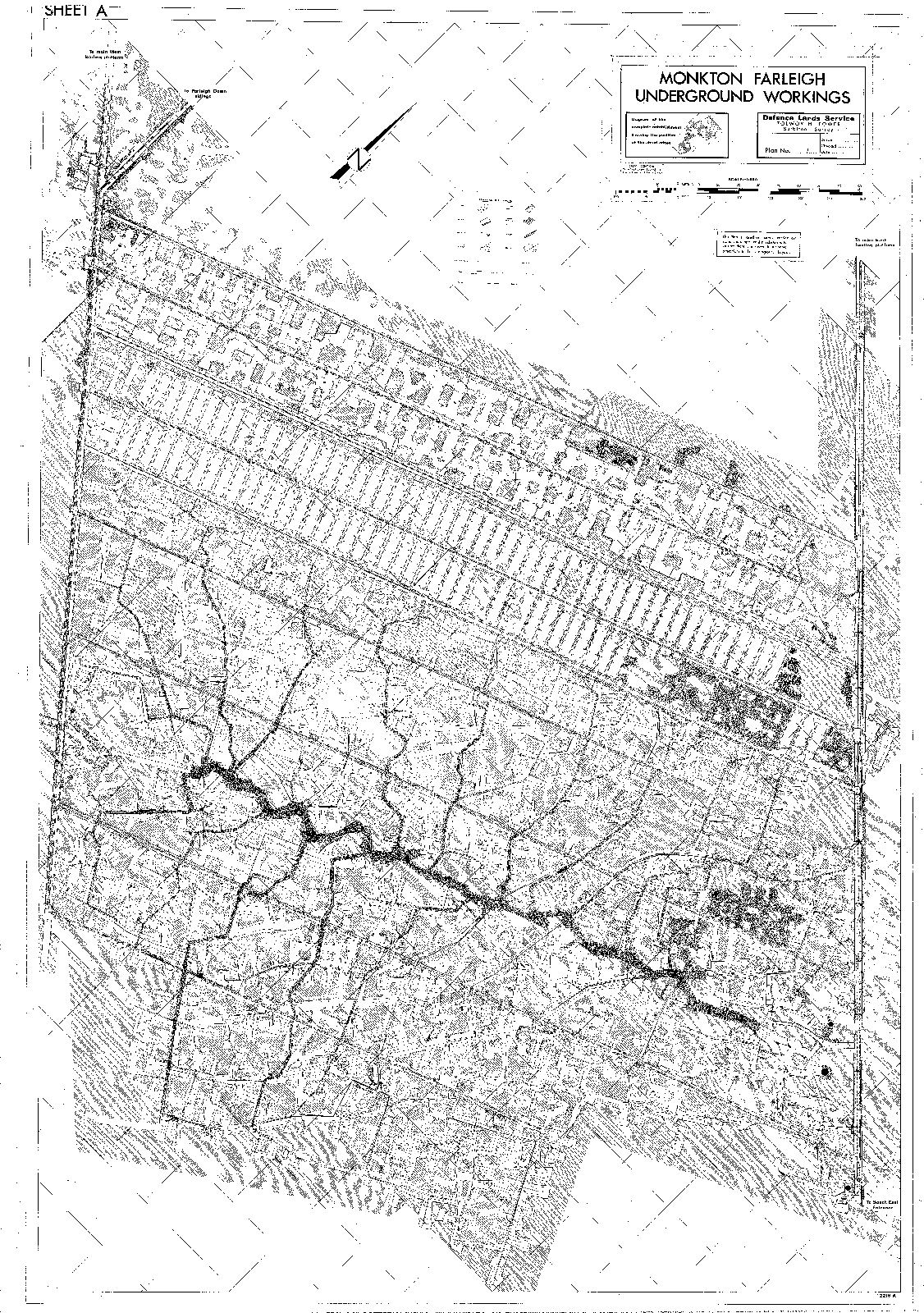

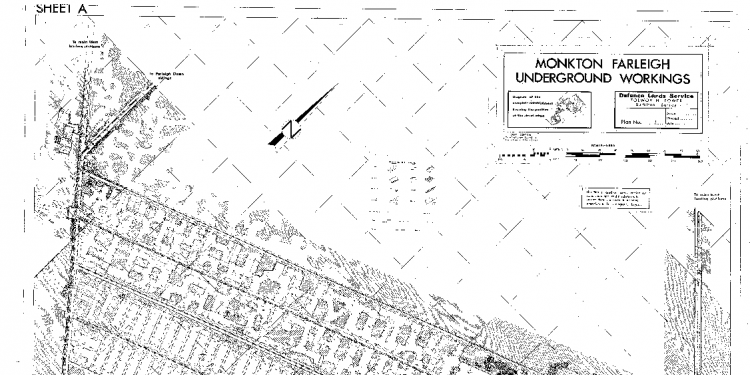

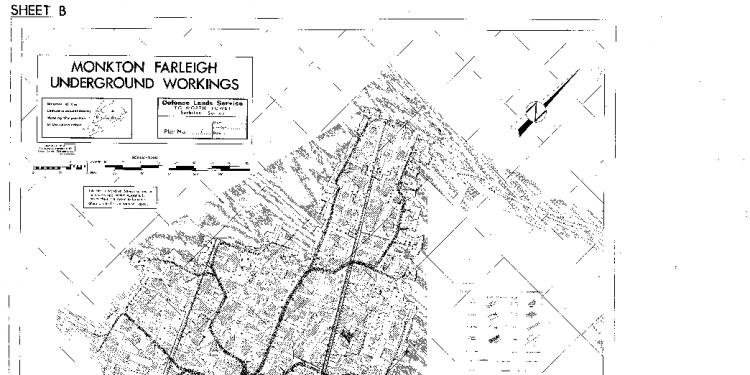

Monkton Farleigh Mine Maps & Plans

Further Reading

Dive into the world of the paranormal and unexplained with books by Higgypop creator and writer Steve Higgins.

Encounters

A historical overview of UFO sightings and encounters, from 1947 to modern government reports.

Buy Now

Investigating The Unexplained

Practical advice on conducting paranormal investigations and uncovering the unexplained.

Buy NowMore To Explore

UndergroundAugust 18, 2008

Browns Folly Mine

UndergroundMay 16, 2014

Dapstone Quarry

UrbexSeptember 26, 2008

Ammo Case Valley

UndergroundAugust 18, 2008

Graham's Grovel

See More on Audible

See More on Audible

Comments

Want To Join The Conversation?

Sign in or create an account to leave a comment.

Sign In

Create Account

Account Settings

Be the first to comment.